The no longer immediate, from the Harold A. Fleming Papers, New York Public Library:

The freshly significant, retaught to us by Photoshop:

The no longer immediate, from the Harold A. Fleming Papers, New York Public Library:

The freshly significant, retaught to us by Photoshop:

“What the hell is this,” he snarled, “a Tom show?”

— Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust, chapter 11

When the posters for this Tom show came out of their lithograph press in 1898 they were stacked face to face. The damage to this surviving example has been permanent. It is still marked with the ghost of another face, in reverse. So far, however, damage has made this piece of printed matter more readable, not less. The ghostly countertext makes us work more productively at seeing the survivor, and as the paper has turned brown it has contributed shading after shading of new complexity to the survivor’s spectral record. The parade is more intelligent now.

In 1898, on the street, it was some horses, some mules, some dogs, and a model house made portable on a wagon. In the mind, it was a communication from a text off-poster — a text whose full title was Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly. There, off-poster, the on-poster word “sumptuous” seemed not to refer to anything. But in 2017, with all sense of what “sumptuous” might have meant in 1898 obliterated by what’s called progress, the palace cars can be seen as such, only as elements within a picture. And there, now, solely within the picture, at last! the palace cars have become one with the classical architecture of their mounting: in an ideal approximation of color, their shading completed by the passage of time, no longer on a mere overpass but on a plinth, no longer cramped smelly boring as they would have been in 1898 but, as the poster’s words promise, regal. In 1898 the pageant was a crudely literal play within a play and Al. W. Martin’s employees with their mule-propelled cabin were only rude mechanicals like Bottom and the boys in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In 2017, surviving through time as a provisionally immortal snapshot, the pageant is seen at last as snapshot sees: mules and dogs and little black actress, stilled in transit toward us, passing just now and forever beneath a palace in the air.

Having become a fossil, the mammoth production invites us to enter its matrix and see it within lithograph stone.

Source: Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014636392/. Photoshopped.

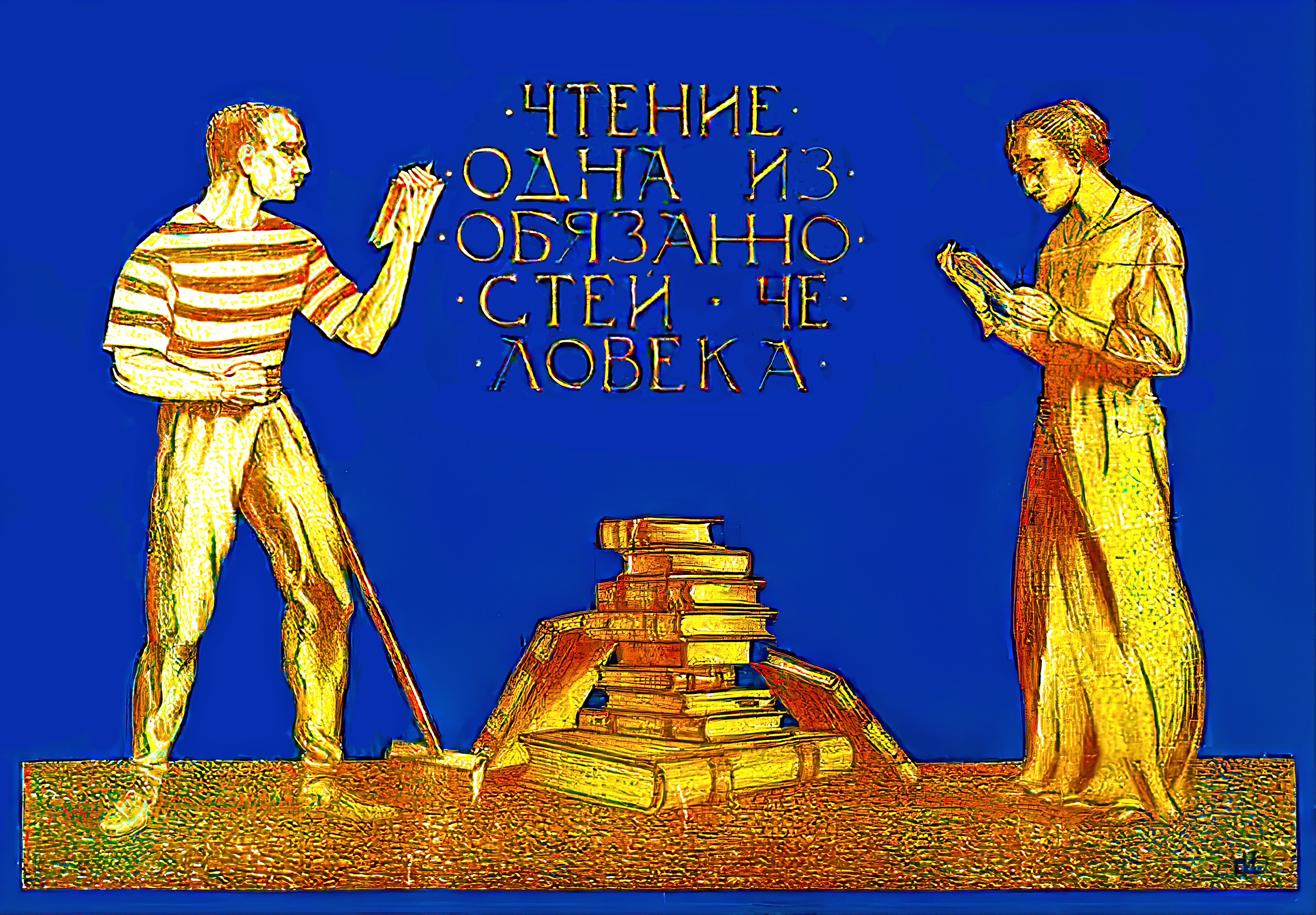

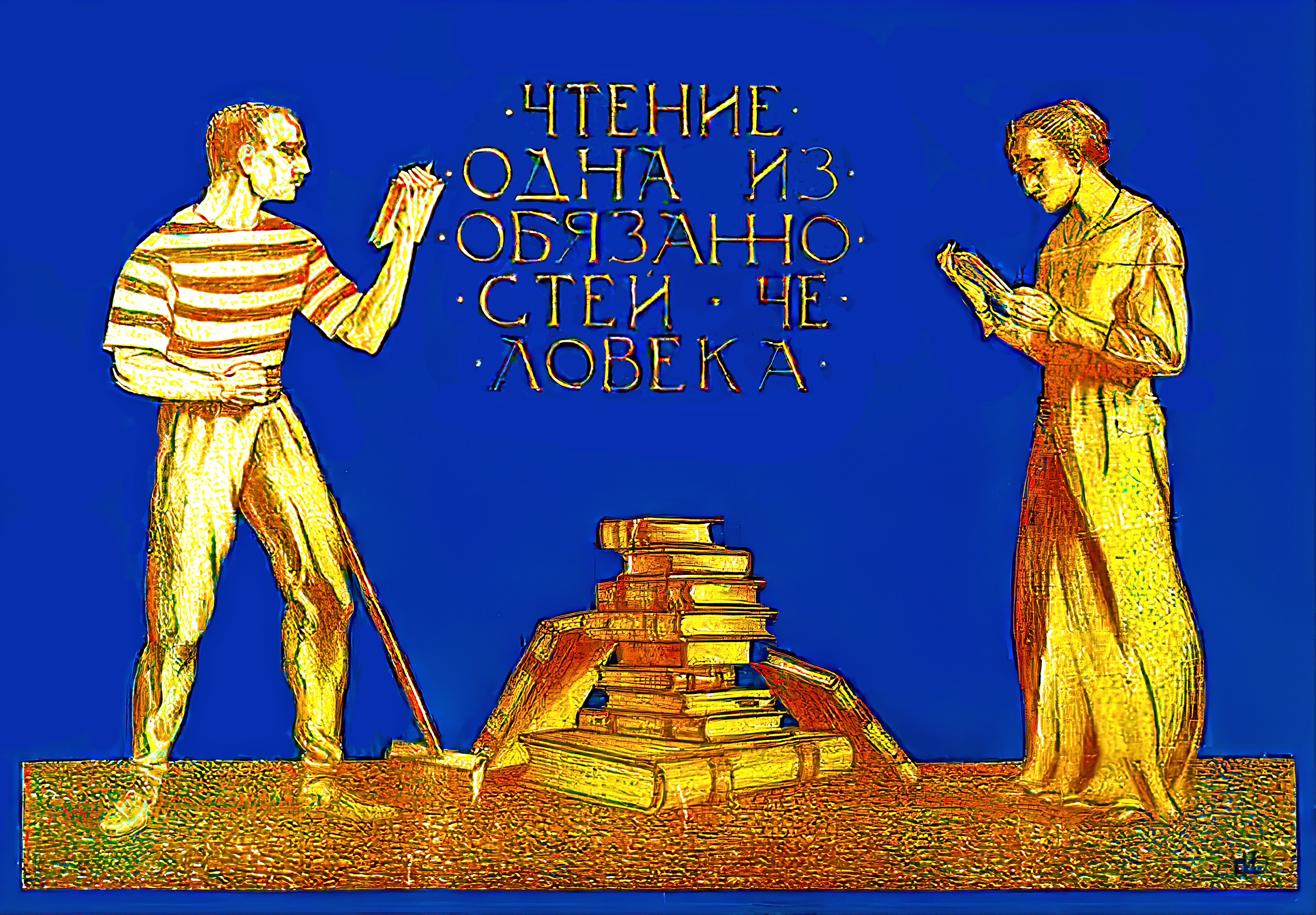

“Reading is one of the obligations of a man.”

“Reading is one of the obligations of a man.”

Russian Revolutionary Era Propaganda Posters, Harold M. Fleming Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-401e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Artist: S. Ivanov. Published 1920. Photoshopped.

“The illiterate is as a blind man. Failure and unhappiness await him everywhere.”

Russian Revolutionary Era Propaganda Posters, Harold M. Fleming Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-4051-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Artist: A. A. Radakov. Published 1920. Photoshopped. The big word in the bottom margin translates as “Books,” but I can’t make out the rest of the text.

Russian Revolutionary Era Propaganda Posters, Harold M. Fleming Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-4027-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Artist: N. Pomansky. Published 1919. Photoshopped.

The headline reads, “Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. Workers of the world, unite. Day of Soviet Propaganda.” The caption reads, “Knowledge for all!” The four books behind the librarian’s peasant-booted right heel are titled History of Bondage (or History of Serfdom), Socialism, Capital, and Class Conflict, and the book behind his left elbow is titled History. The names on the pediments of the buildings are University, Academy, and Library.

But no, she isn’t a teacher. The large imperative painted on the foundation of her blocky columnar image translates as “Serve the people!” and the title of the document in her hand is “Deputy’s Report.”

American reader, you probably had two reasons for your vocational mistake. The obvious one was the image’s heavy didactic freight: its books, its colored pencil, its wall poster in simple educational colors. A more specifically American reason may have to do with the woman’s peach-tinted blouse and mannish little bow tie. It evokes apple-for-the-disciplinarian motifs from folk memory. And of course this disciplinarian is a woman, like most American teachers in 1950, when this poster was published.

But in Russian the peach is heavily overlaid with gray. In the gray, shoulder pads are dominant. It is only down beneath the thick layer pad that the peach-tinted body gestures toward something aspirational off to the right. In another art domain, that unseen ideal could conceivably be a body consisting only of flesh or an image consisting only of cloth covered by paint. The peach-colored Russian woman was painted long after Duchamp’s French woman descended her staircase. But unlike Duchamp’s lithe nude, this gray-swaddled body fills the image from side to side, hugely. Crushed to the margin, nothing unpadded could survive that mass. Its report will be an onslaught. Outside the image frame, the unseen idea of an image consisting only of form will shrivel and vanish. Its unseenness will take on the final trait of inconceivability.

Source: http://thesovietbroadcast.tumblr.com/post/156628250604/1950-serve-the-people. Photoshopped.

Translations:

The text of the Russian poster, created by Georgi Pashkov and published by the provisional government in 1917, reads, “Subscribe to the freedom loan. The old system is defeated. Build a free Russia.” But the loan was a war loan.

The text of the Austrian poster, created by Maximilian Lenz, reads, “1914-1917. Subscribe to the sixth war loan.”

Put on your suit of Rhodesian wool and costume your senior retainer in her native garb. Then board a vessel flying the burgee of the Korean Mail Steamship Company, hoist anchor, steam toward the Peninsula, and conquer.

Source: http://pinktentacle.com/2010/05/japanese-steamship-travel-posters/ , photoshopped

In an art of movement we have no reason to devote our particular attention to contemporary man.

The machine makes us ashamed of man’s inability to control himself, but what are we to do if electricity’s unerring ways are more exciting to us than the disorderly haste of active men and the corrupting inertia of passive ones?

Saws dancing at a sawmill convey to us a joy more intimate and intelligible than that on human dance floors.

For his inability to control his movements, WE temporarily exclude man as a subject for film.

Our path leads through the poetry of machines, from the bungling citizen to the perfect electric man.

— Dziga Vertov, “WE: Variant of a Manifesto” (1922). 100 Artists’ Manifestos From the Futurists to the Stuckists, ed. Alex Danchev (London: Penguin, 2011), 213-14.

The acknowledgment section of Alex Danchev’s valuable anthology is human in a way that makes you want to applaud Vertov’s chorus line of dancing saws. Most but by no means all of Danchev’s bibliographical citations are set down in the order of their authors’ appearance in the book, without page numbers, and if his Vertov chapter has a named translator or source, I lost them in the confusion. No doubt: if you want your book orderly and alphabetical, with no acting out in the front matter, your best bet is to ask a machine.

Generalizing from what he saw, Dziga Vertov renamed his thinking apparatus “Kinok” (kino + oko + chelovek, “movie + eye + man”) in order to suggest that machines can fly us free from the limitations of our own clumsy humanity. Vertov also happened to live in a society where it appeared for a while that the commissars understood machines that way too. Certainly they did speak in machine language.

V. Dobrovolsky (1939), “Long live the mighty air force of the land of socialism!”

http://webexpedition18.com/articles/the-art-of-propaganda-retro-soviet-posters

Click to enlarge.

For the word aviatsiya in this poster’s caption, the Russian-English dictionaries I consulted offered me a choice between “aviation” and “aircraft,” and I adopted “air force” only after correction and contextualization by the Slavicists posting under the names of Hat and Moskva at http://languagehat.com (comment stream, 8 May 2011 post “The Little Seagulls.” Thanks!) But before I had gotten even that far, I was uncertain about Da zdravstvuyet, the imperative that starts the image’s caption. Long live the air force? Your health, air force? That would be the literal translation. No doubt the idiom works better in Russian, a language with grammatical gender where airplanes are masculine. ¡Viva!

However, this moth-shaped little red airplane does seem to be unambiguously alive, doesn’t it? To a Russian in 1939, to a Dziga Vertov, it would even have a claim on the family’s love, a name, and a nickname: the Polikarpov I-16 “Donkey,” stalwart in the Republican air force during the Spanish civil war. But we don’t need to be part of the family to think that those cute little wings are flapping as they bring the airplane up to our face for a kiss. Down on the ground, unable to see or understand the kiss, grownups are marching in neat rectangular blocks that pass around the Kremlin and then drift into larger blocks like floes in a river. We can’t see individual faces there, but we don’t need to. Formed into squads at ground level, they are the base that supports a single airborne image, and down there they’re interchangeable with any other rubble.

At the beginning of Triumph of the Will, the shadow of Hitler’s

airplane (circled) descends over a pavement of marching Nazis.

But we who wait for the little red airplane are watching from a high branch, far above the adult flagstone. We are in the airplane’s nest, and the little airplane is flapping its mighty way home to us.

Dziga Vertov called that emotionally charged machine motion kinchestvo, a word that translates as something like “movieness.” It was his way of imagining the body language of a society fully socialist. As an image, his conception could have looked something like Alexander Rodchenko’s famous poster for Eisenstein’s Potemkin: a dynamic geometry from which the human has been expelled: dumped over the side to drown in a stern Euclidean cosmos.

“Battleship Potemkin. Director, S. M. Eisenstein.

Cinematographer, Eduard Tisse.”

But not long after 1925, the year of Potemkin, the social geometries of Rodchenko and Vertov were suppressed in favor of the paysage moralisé of Socialist Realism. Rodchenko and Vertov envisioned a universe liberated from the human, or at least liberated from what the human had been until the Bolshevik Revolution, but Socialist Realism loved its machines in a cozier way. Socialist Realism inhabits a Disneyfied cosmos, and the simplifying single-point perspective prevailing there welcomes vision in and then lovingly prevents it from escaping.

The words in Rodchenko’s battleship poster have become part of the battleship. They are weapons, and they have struck the falling officer. He is now about to fall through the image plane and vanish. The arc of his fall teaches a geometry of terror. But in the Socialist-Realist universe there is no such teaching. It is not allowable. There, beyond a horizon drawn through the human, nothing may be conceived. Beyond the state, visualized as a march in ranks around the Kremlin and then back and around again, nothing. Beyond visual forms conceived in literary terms, as characters in a fable situated in space by a moral caption (THE LAND OF SOCIALISM!), nothing.

Likewise, for policy reasons: after the pure kinchestvo of Vertov’s Man with Movie Camera (1929), nothing. Man with Movie Camera is a dance of saws, but the last of Vertov’s Three Songs About Lenin (1934) is nothing but a twenty-minute version of the Kazakh national anthem at the end of Borat. Like the poster depicting mighty aircraft moved like marionettes along the illusion lines of perspective, Three Songs about Lenin is flat. It cannot move toward us or away from us. It is held flat against its screen by men in uniforms.

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-2809965914189244913#

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=6900815472005941642#

But the history of its flattening comes to us now with a cheerful moral, delivered airmail. In what’s called historical actuality, the cute little Polikarpov I-16 was an efficient dealer of death: “the world’s first cantilever-winged monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear,” according to Wikipedia. Man with Movie Camera probably has the power to destroy too, just like Rodchenko’s gun shapes. But the change from Rodchenko’s primary forms to Dobrovolsky’s aerobiedermeier tells us that after just one look at the poetry of machines, the commissars decided that they much preferred the comic books of the human.