ship

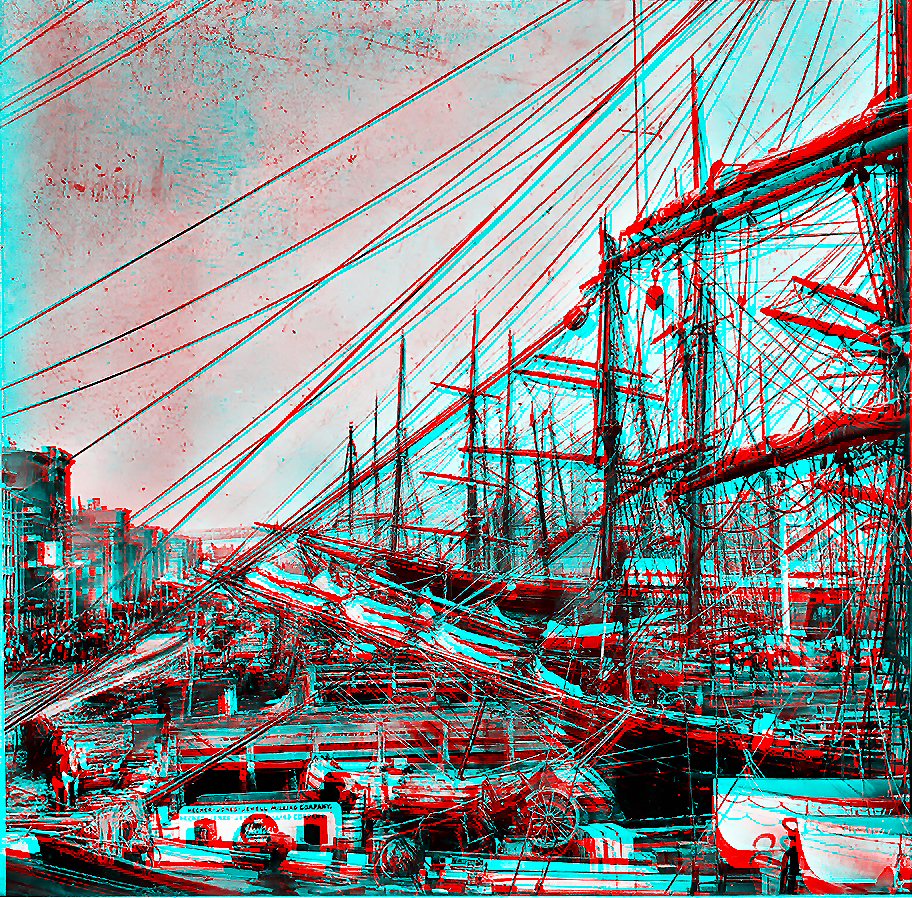

Days of 1908: proof of Cavafy concept

In a corner of an image

an incidental detail which includes a cloud of steam vanishes at the instant of its passage through time into memory. But thereby it entrains itself in forever.

The cloud cycle

Snapshot photography: a facility of transit connecting to Flowerville

Just before dawn on June 17, 1904, home at last at 7 Eccles Street, Leopold Bloom thinks forward in time to an ideal Ithaca. Made ampler by the rich knowledge gained on June 16, the log of his adventures will now include these further chapters.

Simultaneously, in James Joyce’s Trieste, a ship named for the city of Bloom is setting forth. It already exists in a state of snapshot photography. From now on, as long as English or Greek is spoken, setting forth on the tide for Flowerville will always be what happens on the Adriatic coast of time.

Bronze; Ovid

Every rivet has now been hand-hammered into place. Exile through space and time has taken on form. It is ready to commence.

A poet is in transit.

Gesticulations from the age of steam

Three weeks into the Armistice, the dazzle painting still at its work of making illusion;

the hats waved as they had been in the days of plume;

perhaps a shouted word in a now dead language, such as “Hurrah!”;

on the evidence of this illusive little history, a belief that war can be over.

Technical note: vision and the passage of history

To repair a historical damage

can be to reset the function of seeing to an earlier state. On the evidence of this artifact, for example, it may be possible that the advent of photographic vision in the nineteenth century didn’t just coincide with the advent of a metal-framed, curtain-walled architecture teaching its era a newly ample definition of the idea soar

but made it conceivable. Suddenly, cameras on their tripods were equipping the vanishing point with an azimuth and an elevation. Seen in restored state, this image reenacts one of those nineteenth-century instants when sight realized it could sail forever toward an ever receding horizon.

Body language at the end of the long nineteenth century

This cover opens to reveal the dinner menu for Friday, March 1, 1901, on board the world’s first purpose-built cruise ship, the German yacht Prinzessin Victoria Luise. The generic lithograph on the cover doesn’t depict the princess, but she was a pretty boat indeed. Here is the way Michael Zeno Diemer, the Oberammergau portraitist of ships and zeppelins, imagined her as those who bought their passages in her must have felt she deserved to be imagined. When we are on board, of course, imagination is the only way we have of seeing the vessel that bears us.

But in the physical, outside the realm of imagination, we at least can see what is physical of ourselves, and try to make those images approximate themselves to the beautifully comprehended images that we imagine. Our dinner on March 1, 1901, would have included turtle ragout and strawberry ice cream, followed by music of Wagner, Bizet, and John Philip Sousa. So perhaps, after that experiment on the senses, we might have gone sightseeing on deck, in the dark.

You see how we have posed ourselves there. One of us is languidly reclined in spotless spats. Another has painted himself into an icon of energetic masculinity with cap and cape and mustache wax. A third has contracted to something feminine, hugging herself deep inside a shawl. Our bodies and their impelling forces differ, but when they’re on deck together they communicate in a mutually understood body language. Behind us, a huge machinery emitting smoke and green light propels its boatload of bodies, signaling to all destinations that we haven’t yet arrived. We won’t shut down at sunrise, because the sense of sunrise has been postponed. We’ll still be talking when the day dawns on March 2. Silently, without any need for words, our clothes and their bodies will have promised us, that night on deck, that we’ll never die.

—

Launched in 1900, Prinzessin Victoria Luise was wrecked in the Caribbean just six years afterward, a casualty of navigation error. Her captain saw all his passengers safely off, then killed himself.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prinzessin_Victoria_Luise

But for these voyagers transported by the princess through 1901, 1901 is visibly forever. You see that in the remaining record before you. In their lithographer’s presence, the voyagers within the princess became a smiling history of confidence in the everlastingness of dark.

Business with the celestial empire

Native and force