Participial introduction + phrase “she buried her face in” + object of preposition. For example,

or

Participial introduction + phrase “she buried her face in” + object of preposition. For example,

or

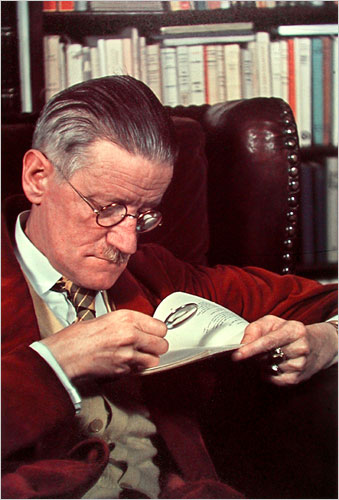

The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), December 24, 1890:

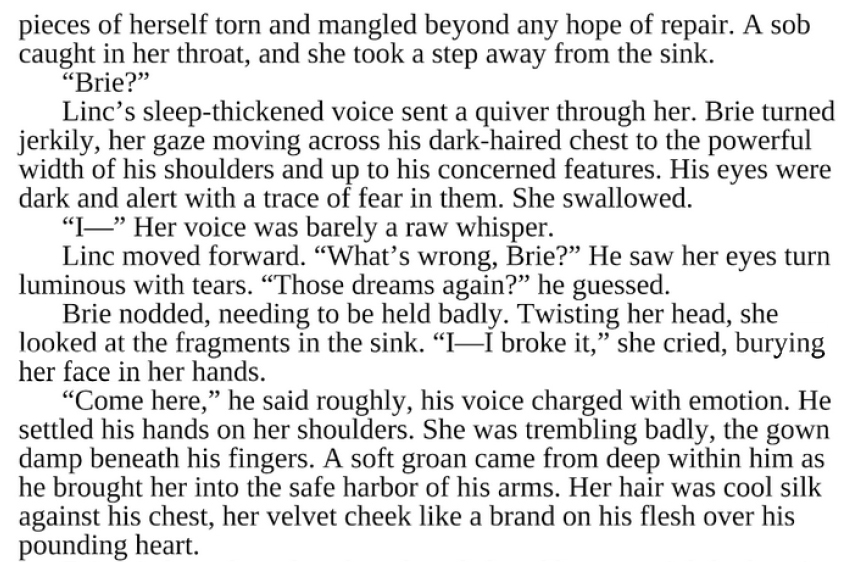

The print doesn’t welcome your presence. But notice that Mr. Joyce himself persisted with the aid of a magnifying glass.

Persist, therefore. Think of yourself as Gabriel at the Christmas feast and afterward, paying attention right to the end.

Clio and Apollo will rest you merry.

10:31 AM:

6:02 PM:

In 2016, all I had to say to get the discussion started about “Self-Reliance” —

What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think–

was “Ayn Rand.” This coming spring, in the Trumpera, the discussion seems all too likely to self-start out of an indignant and rejecting silence.

Still, yes:

Nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal, and one is print. Its beauty is the beauty of his own mind. Its laws are the laws of his own mind. Nature then becomes to him the measure of his attainments. So much of nature as he is ignorant of, so much of his own mind does he not yet possess. And, in fine, the ancient precept, “Know thyself,” and the modern precept, “Study nature,” become at last one maxim.

It’s true, as you see. Nature doesn’t contemplate the possibility of an Ayn or a Donald. In her domain there is only law, reproducing its works by contemplating itself.

Sources: Emerson, “Self-Reliance” and “The American Scholar”

Mr. Turveydrop gives a deportment lesson and decides on the grade.

Dickens, Bleak House, chapter 14

Source: The Modernist Journals Project, http://www.modjourn.org/render.php?id=1425423439777263&view=mjp_object. Photoshopped.

The book is a ten-page pamphlet by the chief prosecutor of the conspirators in the murder of Abraham Lincoln. The prosecutor, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, had attempted to prove that President Davis of the Confederacy was aware of the conspiracy, and Davis’s sympathizers responded by attacking him in print. In print, he replied:

—

Printed in 1866, the paper has gone brown with age. The florid rhetoric looks old as well. Since at least the era of Hemingway, our taste in prose about moral conflict has trended monochrome.

But there were also monochrome effects in 1866. Before, during, and after the black-and-white absolutes of the Civil War, Washington was a Southern town where white was what gentlemen wore in the summer. In the presence of white, both time and the conflict seemed to halt at the wardrobe door. Fashion sometimes looks like a parallel morality, and as of the second half of the nineteenth century one of its commands began, in a body language which seemed to transcend the mortal changeableness of the body: “Thou shalt wear . . .”

Experiment with the command yourself. Think of this photograph of Judge Holt by Mathew Brady’s studio as a frontispiece to the pamphlet. Then ask: after I’ve seen this image of an author’s body in absolute white, will I have any desire to turn the page and read his words’ transient brown? Won’t I lose as much as I gain when I leave the white behind, back there at the innocent beginning where faces are fortunes, books are judged by their covers, and to appear seems to be?

Sources: Holt’s Vindication is online at Archive.org, https://ia600302.us.archive.org/21/items/vindicationofju3693holt/vindicationofju3693holt.pdf.

The photograph of Judge Holt is in the Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/brhc/item/brh2003001193/PP/. I have photoshopped it.