1.

“I saw the hardware store from across the street. I didn’t know you bought flat-irons by the pound.”

2.

The speaker will decide on two, weighing six pounds each. He is The Sound and the Fury’s Quentin Compson, and he will use his purchase to weigh down the body when he drowns himself. The date of the event, in unpunctuated lapidary uppercase, will be JUNE SECOND 1910.

3.

In 1910, customers would ordinarily have bought their irons in pairs as Quentin did. The appliances were made of cast iron, they resembled the fourth of these tokens from a 1935 Monopoly set,

and while one was in use the other would have been heating on the stove. But the metals were changing.

4.

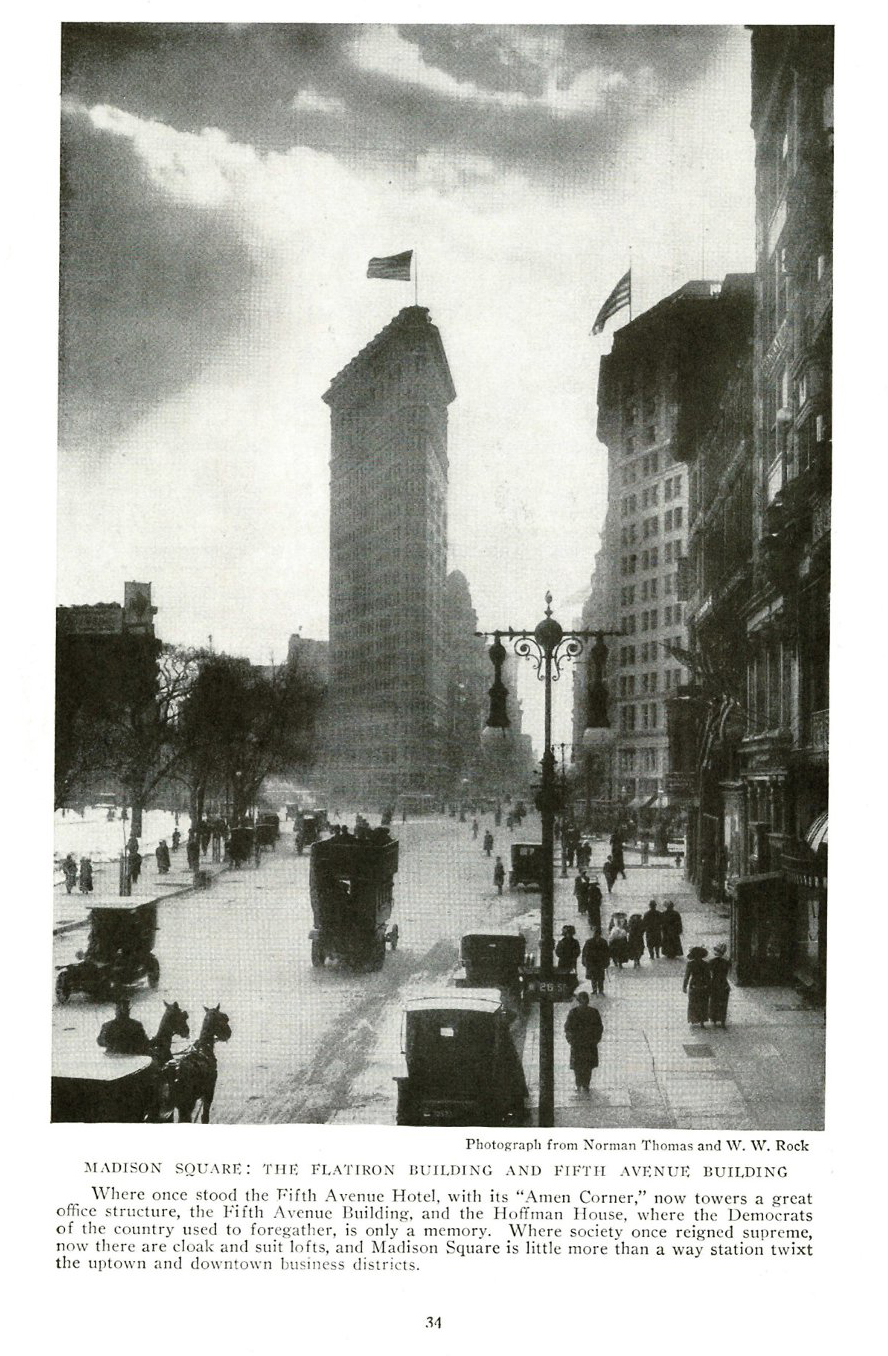

The iron made of iron gave its metonymic name to a building erected in 1902 on a triangular lot in New York formed by the diagonal intersection of Broadway with Fifth Avenue and East 22nd Steet. In 1904, an era when photography emulated what were then called the beaux arts, Edward Steichen shaped this image.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/267803

5.

But compare

See this one contra-Steichen: from top to bottom, starting with the printed date. For a year in a magazine about changing social fashions, that’s a point of origin. As of 1922, for one instance, 1922 was the year when the American novelist Sinclair Lewis published a social satire named Babbitt which by 1930 would make him the first American writer to win the Nobel Prize for literature. It’s all but forgotten now, but in 1922 its description of an evening cityscape seemed memorable. It was full of styles. But just as a matter of professional practice, Lewis didn’t build anything in 1922 that Dickens in 1852 hadn’t built with more imaginative use of material in chapter 1 of Bleak House. More, and decisively: 1922 happened to be a year when the technology of writing English entered a new stage of development. With T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses, a poem and a novel did to literature what the steel skeleton had done to architecture. Babbitt was to remain in the iron age. The Waste Land and Ulysses were wired for steel.

6.

In front of a high steel tower in 1922, a low steel tower moved traffic through gridded Manhattan. Entering stage right, a man in spats and a top hat came dancing through the grid. The zigs of Archie Gunn’s cartoon architecture were now ready to be seen as a jazz.