Source: George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2005024750/. Photoshopped.

myth

The metaphor “a window into the past”

Transport is drawing so close to you now that through its window you can see where behind the Motorman’s shoulder you will ride. Place his obolus in your mouth for the fare and prepare to board.

Transport is drawing so close to you now that through its window you can see where behind the Motorman’s shoulder you will ride. Place his obolus in your mouth for the fare and prepare to board.

Source: Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004677189/. Photoshopped.

Origin and terminus: Louisville, Kentucky, March 5, 1923.

Heritage

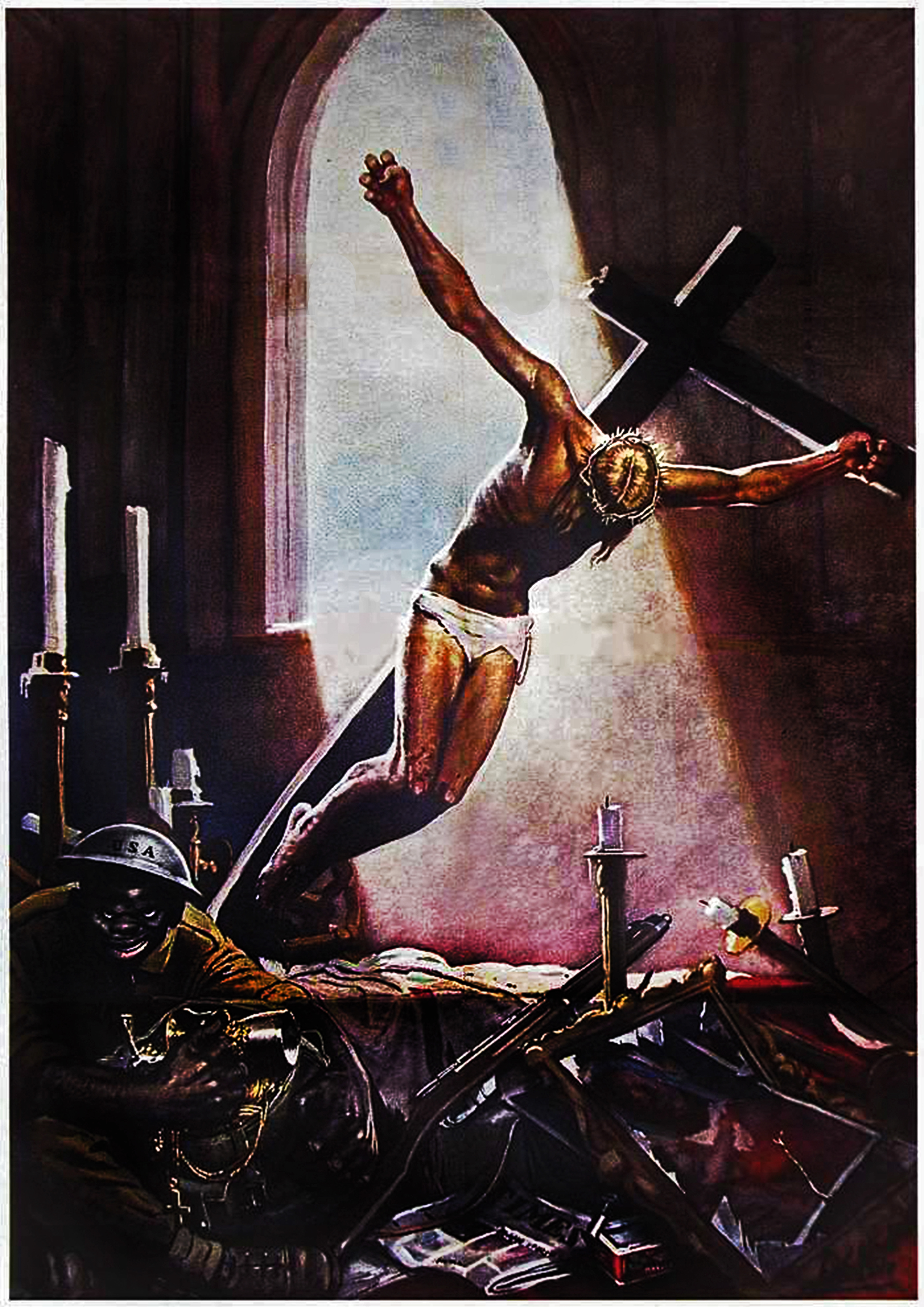

Toward the end of its era, Fascism embarked on a campaign of cultural self-pity. Italy has been attacked by darkness, Fascism told Italy. Everything that Italy has inherited from its past is being violated. In the chiaroscuro, it may seem that nothing remains for us but to grieve. Our candles are out; our heads are bare and bowed before the advent of the black helmets. However, our light will return. Something that will not die bows down to us in our grief and whispers light’s vindicating truth.

But even as the black helmets were making their slow way from temple to darkened temple, the land under Italy’s temples was being cleared day by bright day from the air. Most of the bombers that came flying through the light to accomplish that task of war were Consolidated B-24s, and these bore a propaganda name of their own: Liberators.

In the sheets of light beneath liberation’s radiant onslaught, Fascist art could do nothing except to repeat its now meaningless trope of darkness. Desperate to continue depicting the trope, it once went textual and tried to supplement its now meaningless self with an explanation outside the picture:

“Liberators take liberties!”

Outside the picture, the pun is too witless even to be visualizable. But the image’s trope of darkness retains some meaning nevertheless. Seventy years after the fall of Fascism in Italy, it still speaks to the politics of the United States. It does so because it articulates a myth, and myths are hard to make die.

After all, there can be no light without darkness. That is one sense of the myth of Pluto and Persephone.

That myth says: Light goes down into the underworld and is reborn there from death to life. This will be the happy ending of the art-stories of the looted church and the rape which has been redeemed for art by a successfully understood allusion to Italy’s cultural heritage. When he wrote the history of anecdotes such as those, Ezra Pound was fond of using the word splendor, which means brilliance or radiance. But a splendor returned from the underworld has been in that which is dark, and when it reascends it can never again be immaculate. Bearing shadows within the folds of its mantle, splendor must bring darkness back with it. At nightfall, splendor’s darkness will rejoin the primal dark. Then, after morning comes, we may pick up our brushes once again, seventy years later, and charge them once again with black.

At the present linguistic moment, the Pound-word “heritage” is one shade of that black. Spoken today by reenactors remaking themselves as ghosts on battlefields, it is a word that darkness has taken to itself and refashioned as a mode of immortal yet unliving form.

Look at heritage’s eyes. Look at its pointed fingers delicately touching its slender musket. Understand, as you look, the lesson that heritage is wordlessly teaching you: the lesson that darkness, having once been comprehended by art and shaped by it into myth, can never wholly return, forgotten, to the past and to death.

—

Sources: the Italian propaganda posters come from a collection at http://ic.pics.livejournal.com. The image of the B-24 comes from a site for airplane modelers, Wings Palette, at http://wp.scn.ru. Its Russian caption translates as, “98th Battle Group, Libya, 1943. Shot down August 1, 1943, by [Bulgarian] Lieutenant Stoyan Stoyanov.”

The image “Unidentified soldier in Confederate uniform with bayoneted musket and knife” is in the Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014646219/.

All images photoshopped.

Story

We think the flower looks feminine. Expressed in a medium by an artist, the thought becomes an anecdote. In the museum, a gallery full of Georgia O’Keeffes or Imogen Cunninghams become an anecdote exchange. Soon everybody gets the joke.

—

Linking the sight with memories of stories we read when we were children, we decide that the insect looks armored in bronze. The men pictured in the books had broad shoulders, too. Shortly after that thought has been acted on with a camera, an anecdotal image of the insect begins communicating itself from Tumblr to Tumblr specialized in militaria and inspirational National Socialist anecdotes.

—

The communications become entrained by the economic mechanisms of desire. Getting the joke comes to mean acquiring it on an exchange. The interval during which value is transferred, that epoch between the just-seen subject of a future image and the completed and collected painting en route to a warehouse in the Caymans, is what in a story is called the middle. Into the image below, between records of the moment after one seeing and the moment after another, I insert a pictured page from a story. Click it to enlarge.

Unenlarged between two other images, the image in the middle may resemble the middle term of a single three-part idea, but it isn’t. The panels to its left and the right are wordless souvenirs of the seen, but the middle panel comes to us with an anecdotal pretext arguing that it represents not a seen moment but a known history — in this specific case, the history of the hero Perseus. Guardian and curator of the image, the history won’t allow you to see it as an image. It will impose a context. If the context isn’t visible to the unaided eye, the histoire will slip into its other English translation, “story,” and improvise a substitute out of invisibility. To the left of the middle, there will promptly emerge from the void a panel 1 in which Andromeda’s clothes are being taken off. To the right will emerge the necessary completion of the story, a panel 3 in which Perseus is hauling the dragon’s corpse away to the landfill.

And if you close the handbook of mythology long enough to effect a small change of wardrobe, panel 2 will show itself capable of migration to another story, provided only that the new story belongs to the same genre. The story in the image above and the story in the image below, for instance, are each about a hero. Visually, each is a two-part composition: dark and light, male and female, draped and undraped. The family solidarity of genre even allows the second image to retain its visual integrity after it has been reduced to the status of illustration and humbled by a didactic caption. After all, both the sophisticatedly allusive image above and the demoted image below are histoires. Because they narrate a passage through narrative time with a beginning, a middle, and an end, they transcend depiction in or as themselves. They have a literary history. Just as much as Perseus and Andromeda, the Klansman and his belle refer their meanings at this point in the story to earlier meanings.

(Thomas Dixon, The Clansman)

But the flower on the left and the insect on the right, the images seen only in the moment when they seemed to halt perception with held breath for a moment?

During that moment, they had ceased to become and only were. They had fallen out of the sequence of story. Outside sequence, they had lost their susceptibility to narrative’s power of explanation. We can’t tell a story about the image of the flower; all we can say about it is that during the moment before the words “Once upon a time” could be spoken of it, it may have been in a state of depiction. Supporting a story on either side but capable of referring vision only back to a not yet told story about themselves, such images are not yet readable. And about the moments like those when the told makes contact with the depicted, literary history tells us that after story has been brought face to facing page with a wordless image, it sometimes draws back into itself and goes silent.

At those moments, the story’s words are released from narrative into depiction, there to be seen only as what they are: words, alone or in new associations with other words. I think Pope’s string of naked words, “This long disease, my life,” must have had some genetic homology with the famous glitter of Pope’s eyes. An instant before the words could come to be, the eyes took into themselves the deformed little shape that they had seen in the mirror.

Sources:

Edward Burne-Jones, The Doom Fulfilled. 120 Great Victorian Fantasy Paintings CD-ROM and Book, ed. Jeff A Menges (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2009), image 022.

The illustration from Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1905) is by Arthur I. Keller, online at http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/dixonclan/frontis.html.

“This long disease, my life” is from Pope’s Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot, line 132.

The moment of the gardenia, according to metadata, was June 30, 2014, at 5:48 PM Hawaii Standard Time. The moment of the praying mantis was July 7, 2014, at 12:43 AM.

Words tunneling through the dark. Then light, with the tall figures of the no longer dead. Then dark.

At http://www.loc.gov/item/00694394, annotators have been employed by the Library of Congress to research and write this history.

The camera platform was on the front of a New York subway train following another train on the same track. Lighting is provided by a specially constructed work car on a parallel track. At the time of filming, the subway was only seven months old, having opened on October 27, 1904. The ride begins at 14th Street (Union Square) following the route of today’s east side IRT, and ends at the old Grand Central Station, built by Cornelius Vanderbuilt in 1869. The Grand Central Station in use today was not completed until 1913.

On the camera platform rode a voyager: Thomas Edison’s cinematographer W. G. “Billy” Bitzer. The date of his voyage was May 21, 1905. About the digitized restoration of his camera’s record now visible at

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J10-aYVG6HY,

employees of the Internet Movie Database have written a supplementary history. Reading it as testimony in advance, we suspend disbelief and begin thinking that we are about to see, in good verbal faith, this.

One of the 50 films in the 4-disk boxed DVD set called “Treasures from American Film Archives (2000)”, compiled by the National Film Preservation Foundation from 18 American film archives. This film was preserved by the Museum of Modern Art.

—

We read the words. Words have always taught us to think we know.

But then

Click. See the sudden coming of the light where the dead still live. A moment after you’ve seen it, you’ll be carried off to finish the time you serve in the dark. But as you pass back into the dark you’ll remember the light as if it were a word speaking itself. In its silence, the light will have taught you to hear what words aren’t still enough to say.