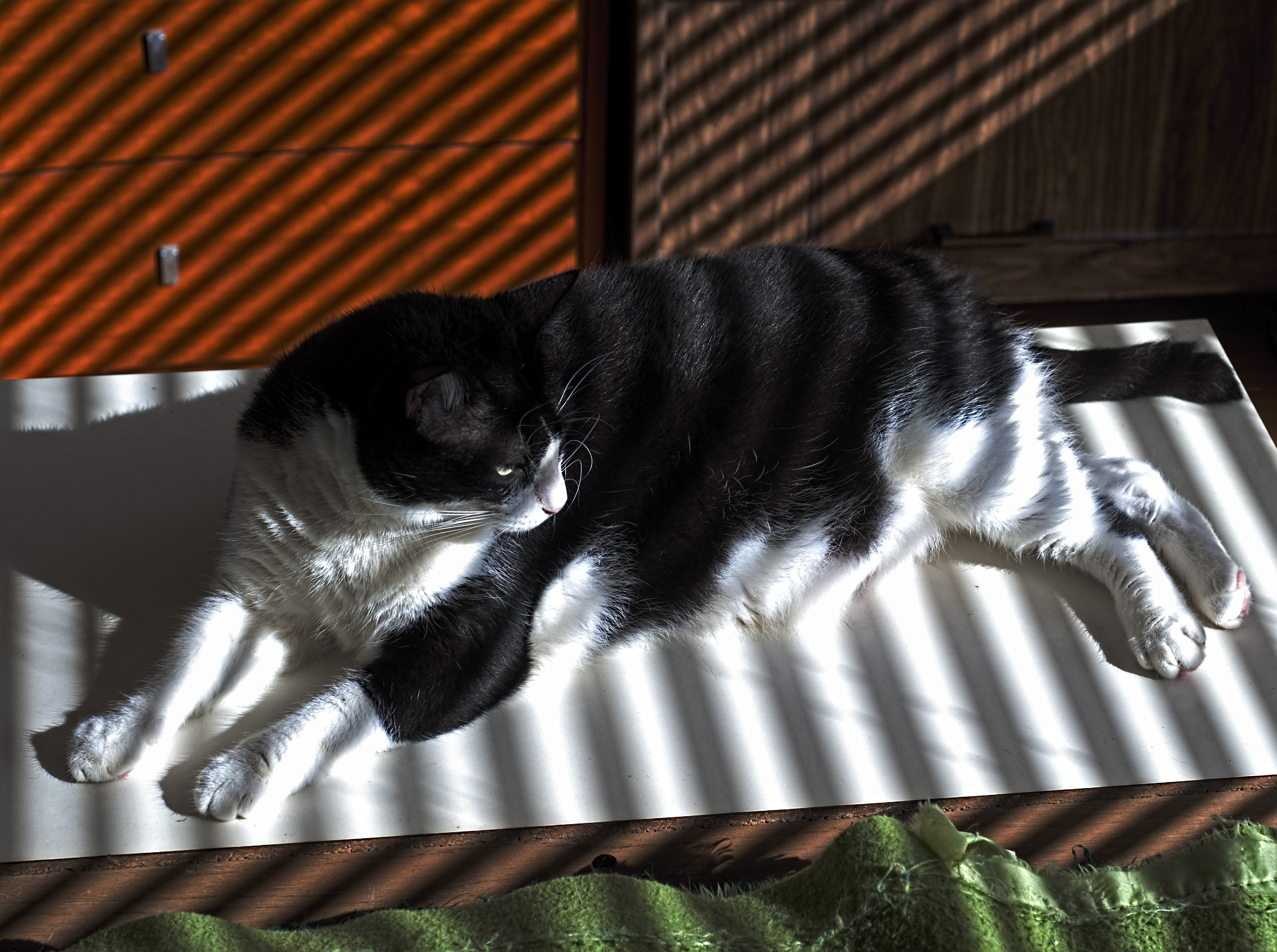

chiaroscuro

Corps: the lighting rehearsal

His domain, the light

Next to godliness

From the series “Thou waitest for the spark from heaven!”

Nevertheless, the kernel of light

You must habit yourself to the dazzle

Sources: “Passenger ship Zealandia in wartime dazzle paint.” Australian National Maritime Museum, https://www.flickr.com/photos/anmm_thecommons/7737510908. Photoshopped.

Whitman, Song of Myself, section 46.

Self-portrait with model in Caravaggio costume

Persons of refinement and good taste

The birth of chiaroscuro

In Arthur Hopkins’s magazine illustration of a night scene from The Return of the Native, the corpse of Eustacia Vye is borne up into lantern-light by Diggory Venn’s shadowed body.

Hardy’s way of communicating the death was to represent a flesh that can be known now only by touch and inference. Covered by her drapery, Eustacia is no longer decently to be seen. In Hardy’s sentence, the dread of death is the dread of something that has now become only palpable. Sensing the change by touch alone, we realize, horribly, that Eustacia is now on her way toward the invisible. But because Hardy’s illustrator had to represent that invisibility visually, he resorted to the technology of literature. Don’t just look at me, says his picture to the readers of Mr. Hardy’s magazine, Belgravia. Start by looking, but then go on to read. Do you remember, for instance, the interpretive corpus you learned in school? Here: refresh your memory by studying this composition.

And the educational process proceeds by allusion. But the labor of study teaches us something else beside evoked literary emotion. Side by side, Hopkins’s picture and its model teach us that narrative art can’t proceed to completion without its handicap aids. To be understood, Hopkins’s illustration requires every one of the words above and below it. Caravaggio’s vision, however, didn’t need to be supplemented,

because the death it depicts is (unlike Eustacia Vye’s) there on the canvas to be seen. It doesn’t illustrate the words of its story; it shines light into our eyes and tortures us into admitting that the light was there from the beginning, before the words.

—

Nadav Kander began his 2010-11 series of nudes by preparing his surface. He dyed his models’ hair red and gessoed their bodies with marble dust, and only then did he turn on the big lights and step back to his camera’s control panel. What that sequence of performances did was to slow a fraction of a second’s exposure time into a realized representation of creation. A Kander woman is a just-shaped mountain, huge hot flesh not yet animated with a pulse or a face. It is whiteness changing into shape under the lights in a studio through whose windows no sun has yet entered. In the darkness surrounding the woman, the first morning has not yet occurred and the first word has not yet been spoken.

We are told in Genesis that evening came first. Only later could there be the kind of light that comes into being when an artist puts down his gesso brush, throws a switch, and says “Now.”