Extremely old Americans may remember that vending machines in truck stop men’s rooms once dispensed condoms whose wrappers were printed with the warning, “For the prevention of disease only.” As textual history demonstrates, that was not just a monition but a commandment. In Connecticut, where Congregationalist Protestantism was the state religion until half a century after the American Revolution, Yankee Calvinists wrote religious laws against birth control in the nineteenth century and Irish Catholics enforced them in the twentieth. The legislative climates were similar in other states, but because a part of art is defiance, defiant literature imagined into being a little paragraph of counter-prose. Getting its hands dirty with latex and ink, literature remolded the words of solemn warning into a mocking anti-sanctimony and stocked cash-operated machines with it under the deacons’ noses.

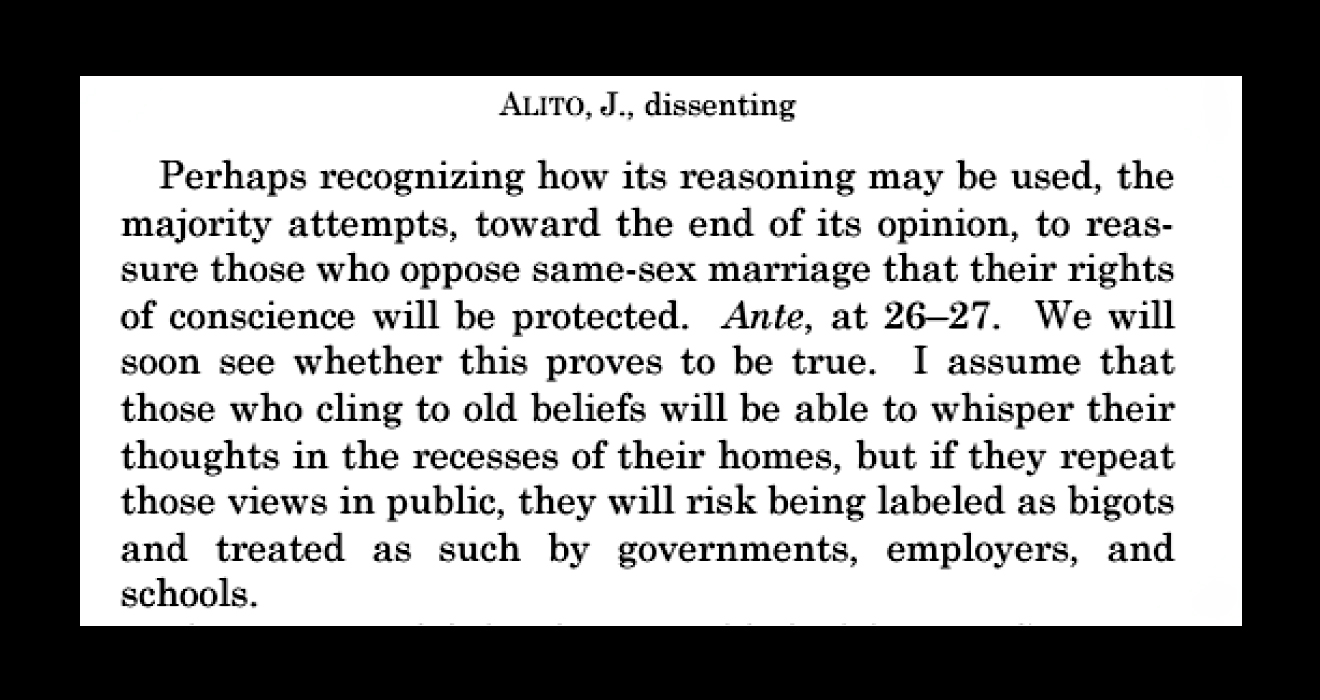

In 1965, however, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Griswold v. Connecticut that people have a right to use birth control for any diseased or undiseased purpose they choose to name, and at that historical point the Trojans lapsed into silence. They’ve remained silent ever since, but it seems possible now that the time will soon return when the men’s room gets noisy as the tiles echo again with priestly bellowings. In 2022, in a concurring opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Center, the decision which reversed the court’s 1973 holding of a constitutional right to abortion, Justice Thomas of the Supreme Court opined that Griswold v. Connecticut must now be reversed too.

Art, however, always anticipates a counter-art. Greek tragedy performed itself in alternation with bawdy satyr plays, and Justice Thomas’s script was anticipated as far previously as 1954, the year Shepherd Mead published his satire The Big Ball of Wax: a novel set in a distant future (1992!), when scripted dreams are beamed directly from TV studios into the brains of the masses. Not all of Mead’s science fiction came true on schedule; his 1992 is still a time of slide rules and carbon paper. On the other hand, a new part of its geography is “St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad), Russia,” and the plot’s key event is that an adman figures a way to get commercials into the dreams. Now that the phones in our pockets are our spying intimates, that part reads like prophecy.

And about that, the cheery satyr-prophets of art invite Justice Thomas, his Christian Church, and every one of the rest of us to unzip a little and dwell on this love scene. Just do the logical thing with the new words that arrive to reclothe your thought, the satyrs suggest, and then what happens after they teach you to speak laughingly will be Happily ever after.