landscape

Synthetic Cézanne: its components

Perspective with vanishing point

Shingles on short diagonals

Catenary straightening in the light

Rounded mountain:

Estampe XXIV: former transports

Source: Detroit Publishing Company Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/item/det1994000820/PP/. 1904. Photoshopped.

Estampe XXI: lightchannel

Source: Detroit Publishing Company Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/det1994014251/PP/. Photoshopped.

War and tree (requires red-and-blue stereo viewer)

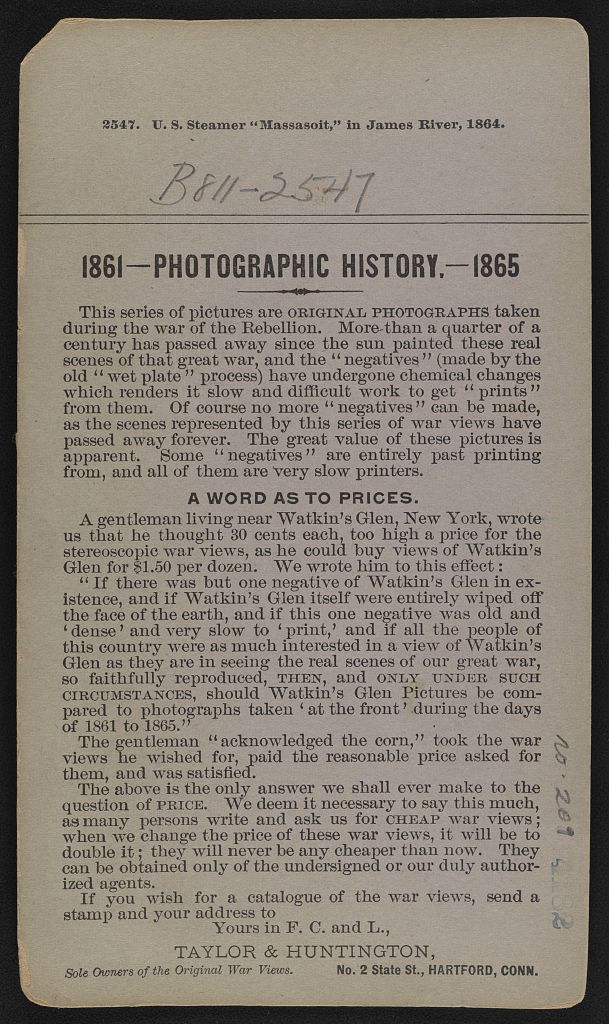

Source: Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011661050/

Valley: the house with the large TV

Landscape with wires and boat

Sunset, Kamiloiki Valley, Honolulu, April 17, 2011

Click to enlarge.

This landscape is a complex of the human and the inhuman, changing as the inhuman light changes around it. Because it’s a complex, it’s available to interpretation and judgment and the partialities of art. But photography’s way of recording the changing sky over a changed ground seems different from anything else available to a human artist. Consider, by way of contrast, this written recording.

The Fitchburg Railroad touches the pond about a hundred rods south of where I dwell. I usually go to the village along its causeway, and am, as it were, related to society by this link. The men on the freight trains, who go over the whole length of the road, bow to me as to an old acquaintance, they pass me so often, and apparently they take me for an employee; and so I am.

The landscape through which Henry David Thoreau travels here is a constructed one with people in it, and Thoreau observes it and the people with all his senses. This passage from Walden begins in the kinesthetics of a solitary walk and expands into the stylized dance of the social. But then, magically, its grammar changes and it makes an escape from anything that might merely be seen, as it might be in a photograph.

Photography, after all, is the art of the indicative mood. It originates in the idea of a fully automatic, fully self-generating art, one in which the human artist is reduced to the subordinate function of middleman between the camera and its subject. Of course that automatism never completes itself by becoming fully inhuman; it’s always interrupted by the moment when a human being decides whether or not to allow the shutter to open. But a human being holding a camera is more anchored to the indicative and its limitations than a human being holding, say, a paintbrush. The indicative will impose its agenda.

The photographer Arthur Fellig, for instance, worked under the byline of Weegee, as in “Ouija board,” because (he said) his agenda gave him psychic powers. The moment a photogenic crime occurred, Weegee said, his elbow would start itching, and that was the agenda’s order to get in his car with its developing tank and contact printer in the trunk, turn on the police radio, and head for the scene. Once he was there, the equipment could take over and carry the agenda to completion. Look, Weegee’s Speed Graphic and flashbulb and high-contrast paper would say then: blood on the sidewalk. But – perhaps because Thoreau’s walk to town along the railroad track is described in the chapter of Walden called “Sounds” – it ends in a soaring upward from the completely seen, in the indicative mood, to the not yet seen, in the optative.

I too would fain be a track-repairer somewhere in the orbit of the earth.

And with the recording of that sentence, photography has been left behind. Photography, it turns out, is an art form incapable of communicating a future tense. In the moments when it communicates wide-eyed with us, what it communicates is only the Little did they know sense of the present learning the truth that the past has been trying to say. Thoreau’s art is an art looking upward from the lighted earth to a not yet illuminated future; photography is an art caught forever on the boundary of blinding light between what we see in the present and what we are about to cease forever to see.

For recording his subjects’ instants on that boundary, Weegee preset the Speed Graphic to f16 and always used flash.

*

About Weegee: http://museum.icp.org/museum/collections/special/weegee/