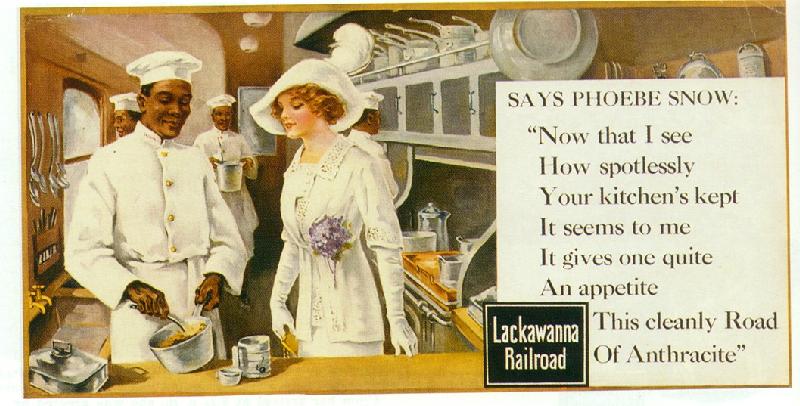

Between 1903 and 1917, a woman named Phoebe Snow traveled like a celestial body along the tracks of one of America’s regional railroads, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western.

Click to enlarge.

The creature of one of the most successful advertising campaigns in American history, Miss Snow existed only to be unceasing: unceasingly in motion along a pounding iambic dimeter, unceasingly white, unceasingly bountiful of her whiteness. In her unceasingness, she was loved.

This illustrated history may help show you why. A comet always arriving, destined never to drop back into the dark and go still, Phoebe lived as light and motion, bestowing herself on everyone beside the track who existed to make her sidereal. Along the path of her orbit, brilliance illuminated the labor of engine crews, yard crews, porters and dining car waiters and the brilliantly white-clad cooks in the dining car’s galley. In her presence, light entered into the interior of what it seemed to mean to be human, dissolving secrecy and shame and shadow into a single all-encompassing whiteness.

http://scout901.hubpages.com/hub/Phoebe-Snow-Railroad-Advertising-Icon

The whiteness released her victims from darkness into love. It even extended underground, to the veins of coal and the men who worked them and the mules who worked alongside the men like brothers of Phoebe’s. There underground, Phoebe became her picture’s source of light. Descending into the dark and then ascending again, she traced letters from light across the darkness, and interpreted them to mean that all will be happy now, even in the face of death.

On August 8, 1914, that consciousness was still alive and still animating a gentleman in love with nature. By then, however, it had abruptly become remarkable. On August 9, a reporter for The New York Times observed it in its descent toward incomprehensibility. Far down now in the third paragraph of an article, it was barely readable by then; too deep in the shade cast by the headline. The language of that headline was a dark new dialect whose words could not have endured in the sunshine vocabulary of Snow.

Not far from the pier, the transatlantic cables surfacing in New York were drowning Phoebe’s meters in irregular sobbings, and Belgian reservists were boarding a ship bound eastward, where the dark was rising.

To understand, then, we have to look away from Phoebe and the gentleman entomologist.. A camera creature has surfaced from the dark flood, extending a black-and-white photograph of the Olympic’s cheering stewards to us.

Source of this image and the next two:

Source of this image and the next two:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2005017010/

The next two have been Photoshopped for contrast.

From this angle in the photograph’s space, the time is the present. The stewards are and will always have been seen to be in mid-cheer. Panning toward the Olympic’s sister ship, the cameraman records the visual testimony of the Belgian reservists singing and cheering back. As they sing, marking time, they are moving outward. The stern of the Adriatic is being eased away from the pier.

That motion has prepared us to receive an image that history, in due time, will call definitive. Now and forever, this image holds us back on August 8, 1914, at the watery verge of a pier in New York. At the far boundary of the space, receding as we watch, the White Star liner Adriatic is now becoming visible as a whole. On board the ship, certain men who will soon die can no longer be seen, though unillustrated abstract history provisionally asserts that they are still, for the moment of August 8, 1914, alive.

In comparison with the blankness into which the ship is now disappearing, Phoebe Snow’s immortally conceived whiteness was only a whim. Anthracite burns cleaner (a little cleaner) than soft coal, but to have believed in Phoebe’s absolute whiteness was never more than a suspension of disbelief. “Of course,” says Phoebe’s image to you, “I am only one of art’s happy ways of helping you imagine possibility. You always knew that.” To have looked at Phoebe’s picture, read her poem, and then bought a ticket on the Road of Anthracite was never a more significant act than, say, buying a ticket to a movie with the cheerful intent of surrendering for a couple of hours to an optical illusion. If Miss Marion Murray had been in this scene, she would have been stationed among us dark-clad neutrals left behind on terra firma, imagining like us rather than being imagined like Phoebe. The optics of this photograph don’t work only on the mind’s eye the way an image of Phoebe does.

Because as the Adriatic begins fading into the dazzle of a hazed atmosphere just at the moment when we take it in, it becomes less visible to the eye even as it becomes more conceivable to the imagination. On August 8, 1914, men and women on a pier and in boats and barges saw a ship loom up through space under clouds of coal smoke and then fade in accordance with the laws of physics. If we could only see it now, we would see it as they did: as a mortal body fading to white, as graceful as it traverses its bright vanishing instant as Miss Marion Murray ever was.