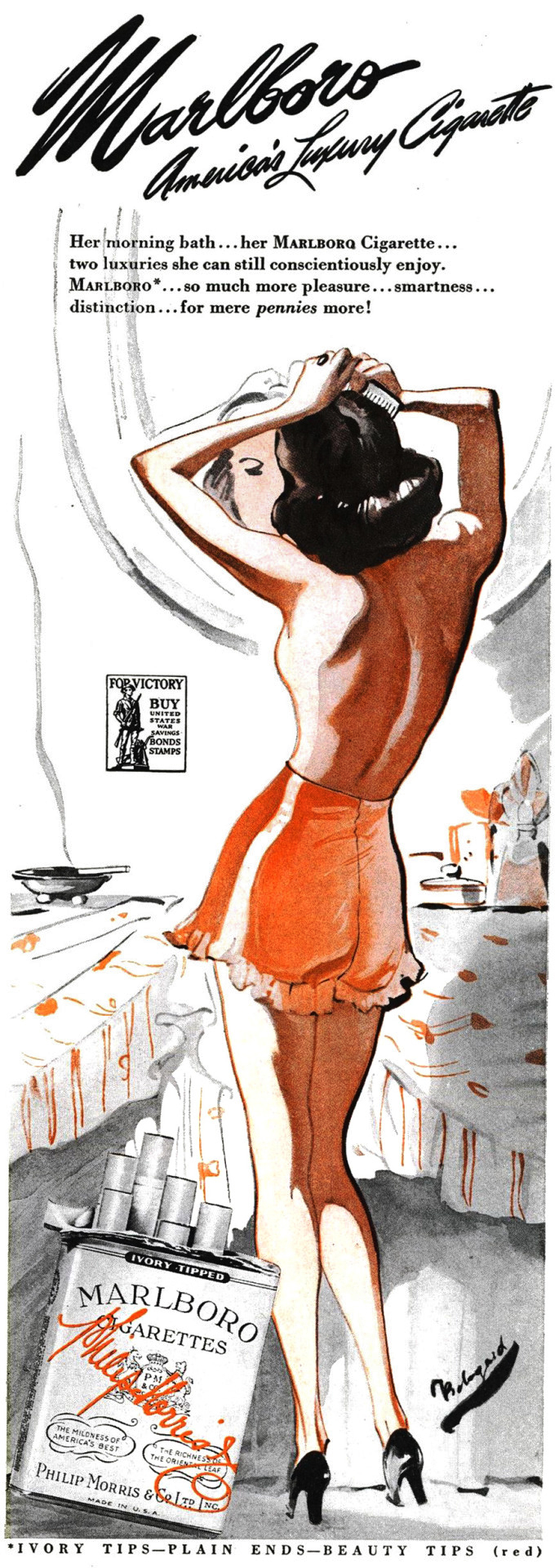

During the early 1970s, Marlboro cigarettes, formerly a niche brand, rocketed to the top of the market and became the best selling cigarettes in the world. The reason is well covered in histories of advertising: Marlboro’s manufacturer switched niches. If the cigarettes haven’t killed you yet, you associate Marlboros with masculinity, thanks to the extraordinary success of an advertising campaign whose icons came coughing onto the page beginning in 1954 — first as men with tattoos, then as cowboys. Look to your left, however, and you’ll see that as of 1944 Marlboros were a woman’s cigarette, tipped with red to hide lipstick stains. At http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php you’ll find a richly illustrated history of the gender reassignment. This note is about a language change that seems to have occurred concomitantly, and perhaps a moral change too.

During the early 1970s, Marlboro cigarettes, formerly a niche brand, rocketed to the top of the market and became the best selling cigarettes in the world. The reason is well covered in histories of advertising: Marlboro’s manufacturer switched niches. If the cigarettes haven’t killed you yet, you associate Marlboros with masculinity, thanks to the extraordinary success of an advertising campaign whose icons came coughing onto the page beginning in 1954 — first as men with tattoos, then as cowboys. Look to your left, however, and you’ll see that as of 1944 Marlboros were a woman’s cigarette, tipped with red to hide lipstick stains. At http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php you’ll find a richly illustrated history of the gender reassignment. This note is about a language change that seems to have occurred concomitantly, and perhaps a moral change too.

Yes, in this advertisement even the illustration has a moral. Between the woman and her ashtray stands Daniel Chester French’s image of the Minuteman of Concord, steadfastly posted eyes-front at breast height. Almost as an afterthought, the advertisement’s text is duty-bound likewise. “Two luxuries she can conscientiously enjoy,” it explains about the illustration, and it half-conceals its heroine’s lineaments of conscientiously gratified desire behind a turned back and a mirror image guarded by a raised arm.

Nineteen-forty-four, after all, was a year when openly acknowledged desire must have seemed shameful. In the sixth year of the Second World War, all of the unashamed rest of America was austere. In window after window hung a little flag bearing at least one star, each star the symbol of a son in the Armed Forces or (if the star were gold) of a son dead on the field. In magazine after magazine, too, the advertisers who articulated the language of America’s economy somberly explained the necessities of shortage and pleaded for willing submission to the unending sacrifice. Turning her back and refusing to look at anyone but herself, Miss Marlboro counterpleaded, with feminine emphasis and a feminine diminutive, for “mere pennies,” but the 1943 penny itself was a memento mori. Not made of copper that year because copper was desperately needed for shell casings, it was minted instead in galvanized steel: no longer the red of a Marlboro beauty tip but gray, gray. “In this refulgent summer, it has been a luxury to draw the breath of life,” Ralph Waldo Emerson had cried with defiant joy as he stood before Harvard’s divinity school in 1838, but 106 years later the threat to joy was no longer a three-quarters-dead regional Puritanism but death itself, fully dressed against the summer in menacing black.

But no, pretty miss in heels and peach-colored panties: even under that dread circumstance, you need not feel ashamed of your bath. It makes you not just clean but clean-feeling, and that harmless benefit comes to you free of any charge, either in money or in currencies of the soul. The world outside has descended fully into 1944, but in this room with the ashtray on the vanity you are about to sink into a bath conscientiously. The original sense of that adverb happens to have been in good conscience.

Postwar, I get the impression that that sense has all but disappeared from American English. The word conscientiously now seems to connote little more than rational but uninspired acceptance of a duty. Yes, yes; I do, conscientiously, try to practice good dental hygiene. But except perhaps as a vestigial technicality in the legal term conscientious objector, any sense of conscience as a motivating joy seems almost to have vanished from English. In 1914, in the first poem of the sonnet sequence he called 1914, Rupert Brooke compared men about to volunteer for the war with “swimmers into cleanness leaping,” but as early as 1918 some of the Englishmen to whom that simile had once seemed to mean something were saying, “Went to war with Rupert Brooke, came home with Siegfried Sassoon.”

So conscience understands that it will be different this time when you take off your panties and leap. But do leap. It seems possible that the calendar will never again advance from 1944, and the leap will at least make you feel clean until you resurface in the smoky air. As a poet who thought himself postwar once sang:

Never such innocence,

Never before or since.

Sources:

http://rbrower45.tumblr.com/post/147185242401/gameraboy-marlboro-ad-1944. Photoshopped.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Divinity School Address”

Philip Larkin, “MCMXIV”