At midday on August 21, 1945, under partly cloudy skies at an airport in Chongqing, China, a recently arrived Japanese transport airplane awaited permission to redepart. Out of camera view, the airplane’s primary passenger, Major General Takeo Imai, was being briefed by Allied officers about procedures for his army’s impending surrender. When he reboarded the craft and its Kuomintang guards cleared it for takeoff, a final change had begun. On September 9, the commander of Japan’s occupying force in China signed a document of surrender and Japan’s colonial empire in Asia came to an end. It had lasted fifty years, from the end of the First Sino-Japanese War to the end of World War II.

It left a photographic record filled abundantly with the kind of images that get called “historical”: the field full of Korean nationalists executed in one of the traditional Japanese ways, by crucifixion; the Chinese mother and her baby being beheaded with a single swing of a Japanese soldier’s sword. But on the tarmac at the moment just before all this was about to end, all that the record shows us in the way of what’s called history is clouds and mountains and an earth indifferently bearing its burden. The unoccupied little Mitsubishi Ki-57 Type 1 takes up only a portion of its history’s didactic illustration, and none of the Chinese and American spectators who surround it seem to be in a heightened state of awareness. Off-camera, the idea of history would insist that this image must be interesting enough to make a moral demand on our attention, but on-camera it isn’t.

Of course time has never taken a break from destroying whatever traces of emotion there may remain in this still-fading, still-blurring photograph. Entropy has claimed some of the image’s significance. Perhaps that’s why I don’t care as much as history tells me I should about the traces that remain.

But at least some of those entropic changes are, for now, reversible. Some of the obliterated traces can be made made to reappear. I have removed what remains of the image from decaying paper to an idea in computer memory, and now . . .

. . . and now, at least, the airplane’s camouflage stands out from the sky. That, however, couldn’t have been the camouflage’s original intent. Camouflage is an art form explicitly designed not to be seen. Dragged into visibility by photographic manipulation, the changed image creates an impression almost of confused, blinking self-consciousness. “Something has happened to me,” it seems almost to say. “I may no longer be what I was wanted to be. I have turned out differently.”

Also, the newly restored cloud-images above the imaged airplane are pushing forward in newly urgent detail, and unlike the camouflage pattern, their collective form has begun proliferating beyond the image frame. To judge from the continuity between this little image-cosmos and the larger cosmos I see through my window when I lift my eyes from the computer, it appears that the image’s cloud shapes remain permanently in persistent vision. They never will change, and so they never will cross mortality’s frontier and enter history. Subsisting forever in the present tense, the unworded object of thought cloud will always just be. It will never become translatable into chronology, because chronology is a text formed by its included intervals of dead time (say, the instants of silence that follow every period) into something always just becoming. Within the wordless image of aircraft and clouded air at which I’m now looking, the only part that is historical is the tableau depicted beneath the clouds, where unnamed and now unnameable soldiers stand with with their backs turned to us. What that turning away says wordlessly is: “From this moment, I am going to be unreadable ever after. Having once emerged for a fraction of a second from the not-yet and shown a photosensitive surface within a camera what I then was, I will never show myself again.”

—

One American war earlier, a patriotic milkman in Richmond, Indiana, took out a notice in the Richmond Palladium-Item to defend his virtue with respect to petroleum. We milkmen stand FALSELY ACCUSED, he cried. “We are,” he cried, “FEEDING THE BABIES OF AMERICA.”

The date was September 21, 1918, and as a wartime conservation measure the Federal government had decreed what it called Gasless Sunday: a ban on Sunday pleasure driving everywhere in the United States east of the Mississippi. Just below the plea from the operator of a fleet of gasoline-powered trucks, the dealer for a battery-powered automobile was letting himself go smug accordingly. “The Seven Day Car,” gloated his self-promoting prose. And it rubbed in the gloat with a moralizing slogan: “The Conservation Car.”

The date was September 21, 1918, and as a wartime conservation measure the Federal government had decreed what it called Gasless Sunday: a ban on Sunday pleasure driving everywhere in the United States east of the Mississippi. Just below the plea from the operator of a fleet of gasoline-powered trucks, the dealer for a battery-powered automobile was letting himself go smug accordingly. “The Seven Day Car,” gloated his self-promoting prose. And it rubbed in the gloat with a moralizing slogan: “The Conservation Car.”

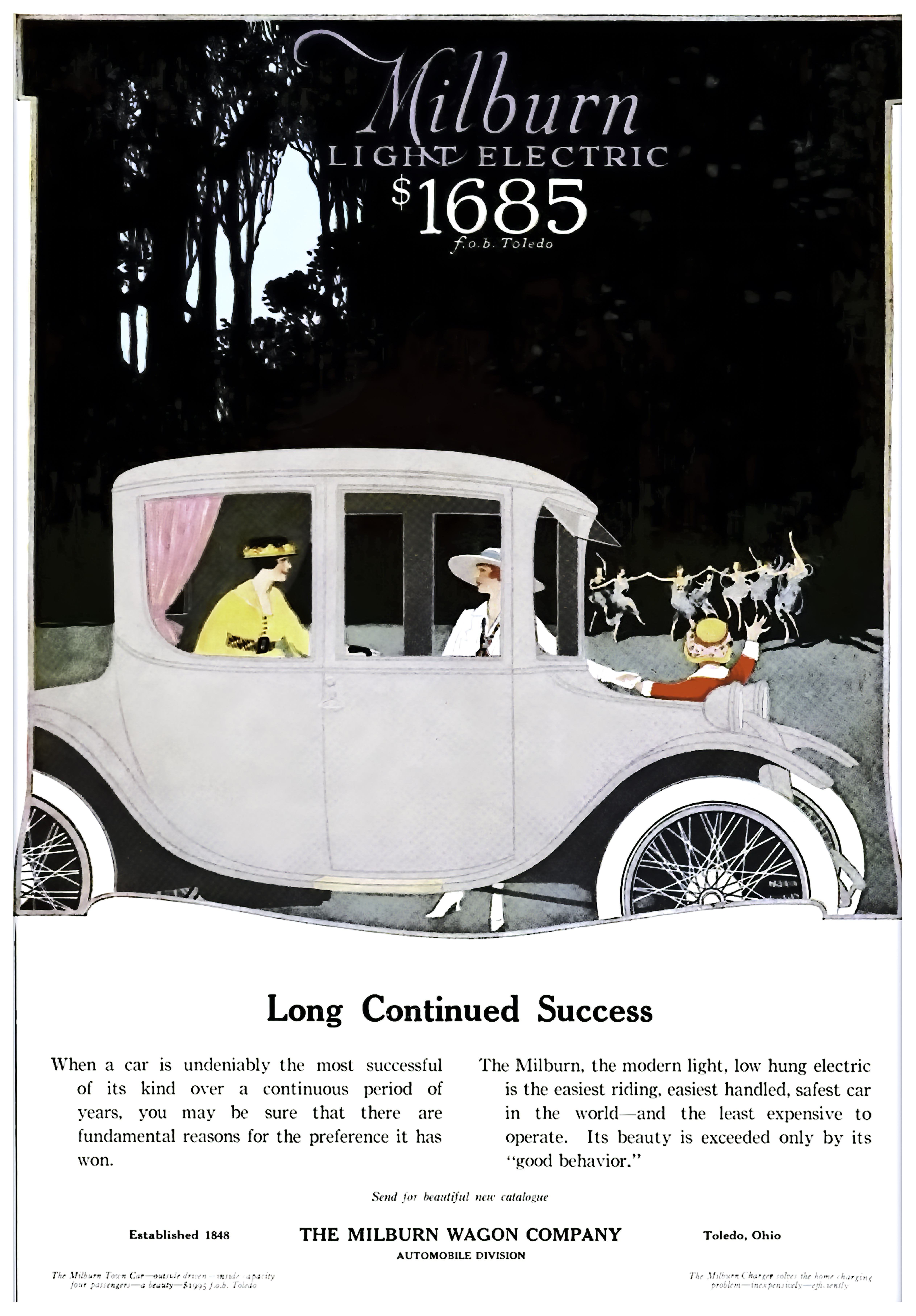

The application-text beneath the front wheel expanded that phrase into a sermonette by drawing attention to the electric car’s now significantly absent gas tank. Then, working back in time to the now inconceivable era of peace, it generalized from automotive economics to the sexual economy that underlies every changing human action. “A few years ago the Milburn Electric was considered an exclusive car of ladies — ” said the analysis, lingering in suspense at the dash in order to let a not yet conceived thought gather itself unseen and then pounce and penetrate, “but today — business and professional men use the Milburn constantly — and in preference to their gasoline car.”

As of September 21, 1918, readers would have assented without argument to the first of those propositions: the undaring, unadulterous one. They would all have known that before the electric starter came into wide use in the middle to late nineteen-teens, electric cars were indeed marketed to women. Electric cars had to be little and they couldn’t go far or fast, but they were also clean and quiet and easy to drive. On the other hand, hand-cranking a gasoline motor was a dirty, sweaty job, and beyond many women’s strength. So, for a while, the electric car did participate in a gendered competition. The Milburn, one of the more successful marques, was in production for a respectable fourteen years, 1910 to 1923, and during the Wilson administration the Secret Service patrolled the White House grounds in a fleet of Milburns. But less than two months after this issue of the Palladium-Item landed on the front porches of Richmond, the Great War ended and Gasless Sunday vanished from the calendar. Soon enough, the electric car followed. When electrics were remembered in later years, they were indeed remembered as ladies’ cars — for instance, by the protagonist of Jean Stafford’s 1948 short story “The Bleeding Heart,” who gets a surprise when she learns that the driver of an antique electric car she has seen is not an old woman but an old man. Inside an electric’s softly upholstered internal space, a male body was anomalous.

So Milburn’s 1918 claim on the love of men was only a fantasy. It was specifically a fantasy in words, born out of resistance to reality and unsustained by any evidence available to sight or memory or male desire. In its favor it had only the fickle military time-term “For the duration.” But in 1917, when Milburn had thoughts only of women, she had at her call a different sort of fantasy: a fantasy self-created not from words but from images and expressing itself through shapes, colors, and the visible traces furrowed by desire along its transit through the body.

Shaded, then, by a delicate openwork typeface through which the breeze whispers her name, Milburn 1917 comes gliding on white wheels into a grove of tall trees planted by Fragonard. There, barefoot on pastoral herbage, dance a troupe of Isadora Duncan nymphs. At their distance from Milburn it will be impossible to hear a shepherd sing his lying song, “Come live with me and be my love,” and the space sheltered just behind Milburn is filled only with mother love: quiet as an electric car, with a little girl in little-girl primary colors restrained safely by her mother’s hand while she wiggles her own fingers in virginal greeting. Like the soldiers in the other image, she has turned her face inscrutably away from us. She must be about her Milburn’s business. As Keats might have caroled from his own darkling grove, she was not born for death.

Shaded, then, by a delicate openwork typeface through which the breeze whispers her name, Milburn 1917 comes gliding on white wheels into a grove of tall trees planted by Fragonard. There, barefoot on pastoral herbage, dance a troupe of Isadora Duncan nymphs. At their distance from Milburn it will be impossible to hear a shepherd sing his lying song, “Come live with me and be my love,” and the space sheltered just behind Milburn is filled only with mother love: quiet as an electric car, with a little girl in little-girl primary colors restrained safely by her mother’s hand while she wiggles her own fingers in virginal greeting. Like the soldiers in the other image, she has turned her face inscrutably away from us. She must be about her Milburn’s business. As Keats might have caroled from his own darkling grove, she was not born for death.

I photoshop time’s blemishes from Milburn’s pearl-gray sides, then step back as she continues her transit across unchanging beauty.

Sources: Both the image of the airplane and the color image of Milburn are found in several locations on the Web, and I haven’t located bibliographical citations for either original. The Tumblr page where I found the Milburn image gives it a date of May 1917, but no source for that attribution is given. My information about the history of the Milburn comes from http://www.milburn.us/history.htm.