As of April 21 my new WordPress blog hasn’t yet been found by Googlebot, but it already seems to be picking up more spam comments in a week than the old Blogger blog attracted in six months. The latest one compliments my brilliance and then extends an invitation to advertise something called Juice Cleanse Detoxify, and the more I look at that phrase in my own blog’s composing window the more seductive it seems.

After all, the notion that the literal or figurative body is a vessel full of poison is not just perdurable but ancient. Walt Whitman, who suffered from chronic constipation, was always writing himself resolutions to purify and then rebuild his body, and the metaphor is prevalent throughout nineteenth-century America, from the writings of the health lecturer Sylvester Graham, “the peristaltic persuader,” to the Book of Mormon. In twentieth-century Europe, too, Gottfried Benn was attacked by a fellow Nazi, the propaganda painter Wolfgang Willrich, in a book which was called Säuberung des Kunsttempels, or “Cleansing the Temple of Art.” In that title the metaphor presumably (I haven’t read the book) comes from the Bible, perhaps by way of Psalm 51: Asperges me, Domine, hyssopo, et mundabor, “Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean.” At the opening of the Mass, the priest symbolically purifies the congregation by sprinkling holy water as he chants that verse.

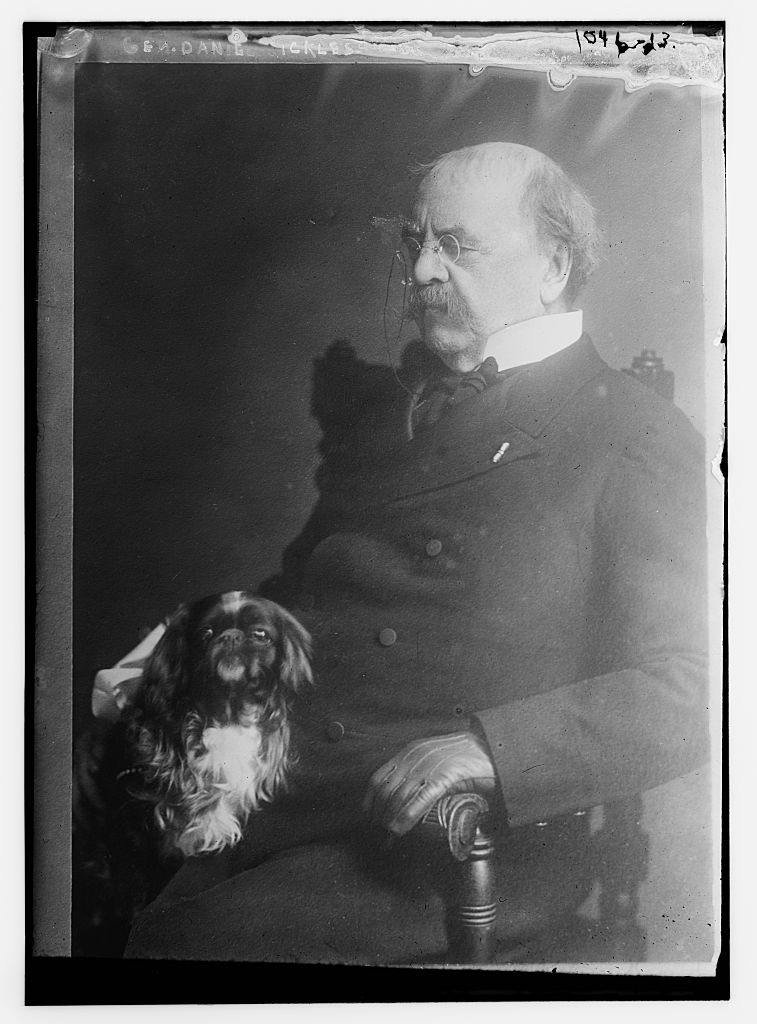

Willrich’s own art was pure in the extreme;

Click to enlarge

Benn’s perhaps less so. Taking notes in wartime like a responsible clinician, Dr. Benn observed one of his fellow officers in the act of commenting on his own language practice — “I command only once” — and then completed the communication by completing the predication: “The subject was latrine-cleaning” (58). That realized a little zone of the world by anchoring its language to the soiled human actuality of a toilet brush. As spoken by the officer, the phrase “I command only once” could have significance only for the officer, but after the poet translated it into what Wordsworth called “the language really spoken by men,” it acquired communicable meaning.

But the art of Willrich’s portrait begins by expelling the really spoken. Erase the black, says this art, and leave the paper white; purge the unclean and leave the perceiving eye nothing to perceive but the clean. Willrich’s head model has been cleaned that way by the artist’s charcoal, and so he no longer senses the persuasions of his lower body. Erased from within, his expression has lost the fascia that once made it move. You can’t believe you could see through that unmoving face into a mind full of thought, as you might believe in front of a portrait by Rembrandt. A head by Willrich has no body, and there is nothing inside it except paper. The paper is a painter’s, too, not a poet’s. It’s blank and wordless.

As for me writing words in the postwar, I dismissed as spam my commentator’s persuasive invitation to collaborate in the ongoing work of cleansing and detoxifying. But thanks anyway for thinking of me, anonymous bringer of hyssop from the ancient world.

*

Work cited: “Block II, Room 66,” trans. E. B. Ashton. Gottfried Benn: Prose, Essays, Poems, ed. Volkmar Sander (New York: Continuum, 1987), 53-63.