Literary theorists call the depiction of depiction mise en abyme, taking the term from heraldry’s coats of arms nested within coats of arms.

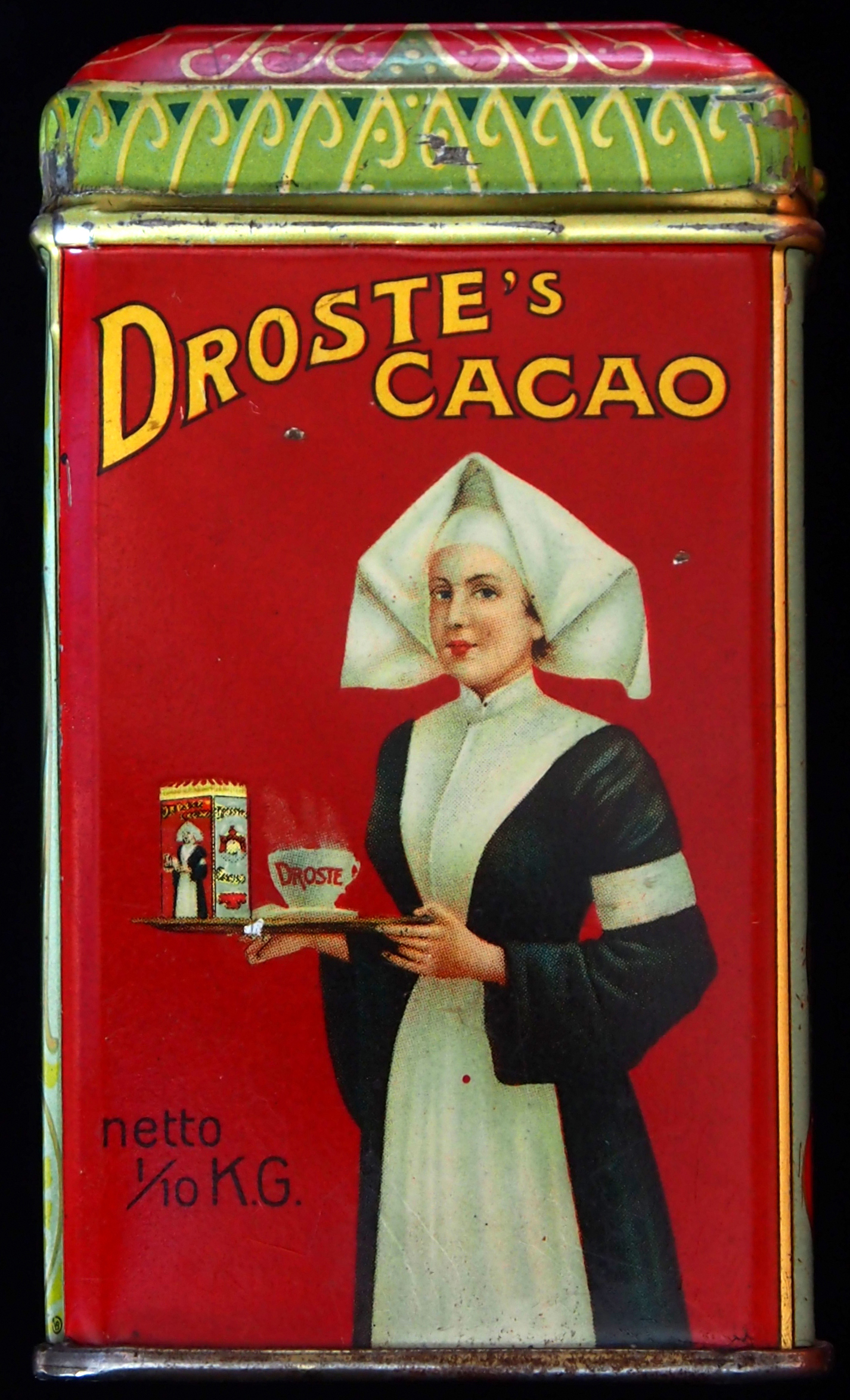

Graphic designers call it the Droste Effect, after a brand of chocolate.

Graphic designers call it the Droste Effect, after a brand of chocolate.

Droste iterations don’t just lock themselves into their series; they lock in our vision too. They impose on us a task that can’t be completed: the task of seeing them. The little girl spilling the canister of Morton Salt on the canister of Morton Salt changes her clothes over the years, but (despite the coyly evasive caption of this advertisement from 1968) she will never be able to carry the change to completion and become a woman.

Droste iterations don’t just lock themselves into their series; they lock in our vision too. They impose on us a task that can’t be completed: the task of seeing them. The little girl spilling the canister of Morton Salt on the canister of Morton Salt changes her clothes over the years, but (despite the coyly evasive caption of this advertisement from 1968) she will never be able to carry the change to completion and become a woman.

http://www.mortonsalt.com/our-history/morton-ads#ad16

http://www.mortonsalt.com/our-history/morton-ads#ad16

As we begin to think we understand the paradox, we ourselves do change — but we change only into Keatses at the wedding feast of the still unravished bride. There at the feast, looking up from the table to catch the eye of Droste’s nursing sister, we may go roguish and ask her, “What is in your tin” — but the moment we get that far, we become conscious of having learned something scary about the limits of our ability to express. Actually, strictly speaking (the nun’s ruler comes down with a whack), what we have just thought isn’t yet ready, never will be ready, to be punctuated with a question mark. It hasn’t become a question because a question entails a terminally punctuated answer, and the series “What is in your tin is in your tin is in your tin . . .” is not that, whatever else it may be.

—

Now look at this other picture of a picture. It’s a nineteenth-century photograph of the kind called a tintype: a direct-positive image that registers on the eye by reflection from the photoreduced silver in an emulsion laid down on a sheet of black-painted metal. Tintypes were generally of low contrast and low quality, but they were popular as keepsakes because they were inexpensive. At the cost only of a small investment, they got busy on their return by helping memory work.

Backed up against her own layer of tin, Sister Droste does the same thing, and furthermore she advances toward memory unprotected by any frontal armor. By contrast, the low-contrast man in the tintype evades direct perception because he is enclosed in a case with a glass front. Between him and us is his pane.

At the Library of Congress, this compendium of things to sense (tin and cardboard and velvet and glass and pigment enclosing an image enclosing tin and cardboard and velvet and glass and pigment) has been compiled under a single archival title, but the title’s first word is “Unidentified.” More title words follow, identifying clues like the flag in the background and the oddly buttoned jacket, and eventually a full-length caption develops: “Unidentified soldier in Union Zouave uniform with cased photograph in front of American flag backdrop.” You can learn the meaning of the term “Zouave” from a military dictionary, and it may also be useful to understand that the Library acquired the image (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2013650144/; I’ve photoshopped it) as part of the Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Such information is limited, yes, but limits are educational too. They let us frame what we know and separate it from the unidentified.

At the Library of Congress, this compendium of things to sense (tin and cardboard and velvet and glass and pigment enclosing an image enclosing tin and cardboard and velvet and glass and pigment) has been compiled under a single archival title, but the title’s first word is “Unidentified.” More title words follow, identifying clues like the flag in the background and the oddly buttoned jacket, and eventually a full-length caption develops: “Unidentified soldier in Union Zouave uniform with cased photograph in front of American flag backdrop.” You can learn the meaning of the term “Zouave” from a military dictionary, and it may also be useful to understand that the Library acquired the image (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2013650144/; I’ve photoshopped it) as part of the Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Such information is limited, yes, but limits are educational too. They let us frame what we know and separate it from the unidentified.

But within this particular frame the word “unidentified” prevents a Droste series from beginning because it precludes us from conceptualizing the enclosed images as a formal unity. Having been named with a word (“Unidentified”), the images now enter our minds as words: words approaching us not the way images do, in simultaneity, but as texts do, one by one, in a sequence whose constituents may or may not be related to one another. The soldier in the photograph may or may not be holding a photograph of himself, but we’ll never know. The cup of Droste will pass from us.

But whatever the soldier is holding now, at the moment of our perception, he holds it up to the pane that separates him from us. On our side of the pane, at this very instant, in bathrooms all over the world, people are busily acting out a belief that holding a cellphone up to a mirror will teach the cosmos what the word “self” means. But on the far side of the soldier’s unreflecting little slip of antique glass, Narcissus himself has gone invisible. One tantalizing moment after a hand behind the pane has beckoned to us, the pane goes unbreakable and the unidentified All behind the pane goes permanent.

Or, as Keats put it in a little shard of a poem that he didn’t get to protect from touch behind glass before he died:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d — see here it is —

I hold it towards you.