In Girodet’s Apothéose des héros français morts pour la patrie pendant la guerre de la Liberté, the heroes, some of Napoleon’s favorite generals, are shaved and bathed and unsullied by their wounds. They’re in uniform, too, as if they had never looked like anything but generals, and at their moment of apotheosis they are no younger than they were at the moment of their death.

Moment, singular. According to their group portrait, that moment occurred just once. At that moment, each hero became forever an element of a composition whose medium was rigor mortis. At the moment of death, each hero became perpetual. With his promotion to Statuary General, he lost the Other Ranks’ privilege of changing his clothes.

Likewise, Girodet’s statuary Ossian is old and blind as he welcomes the group representing sculptured military middle age, while the Rhinemaidens or whoever they are are moisturized and young even though they too are statuary. That’s how the picturesque does elegy. It’s a technique for making visual the idea of simultaneity that is communicated by the elements on either side of the conjunction and in the prayer, “Now and at the hour of our death.”

—

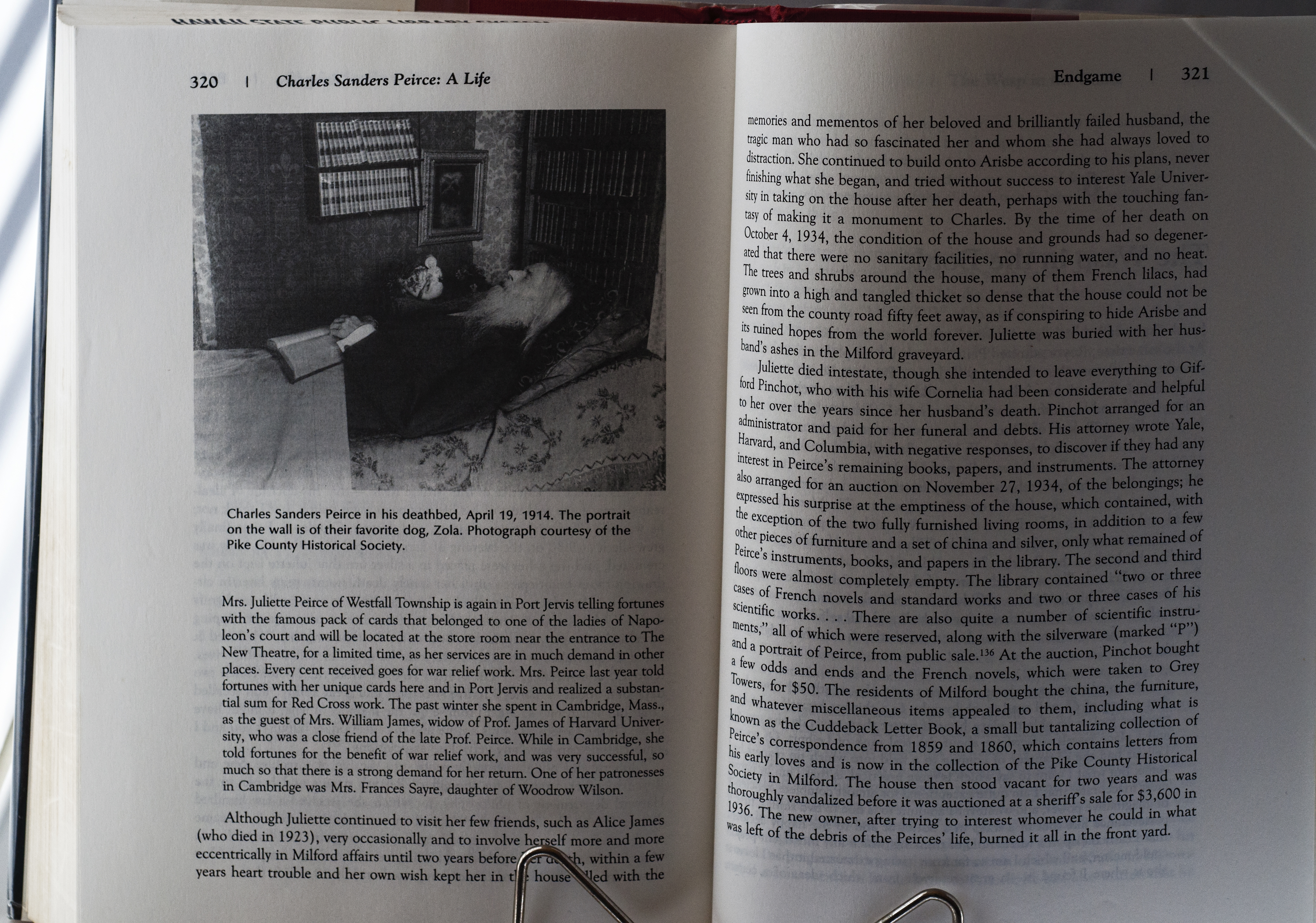

When the troubled genius Charles Sanders Peirce died in his eccentric edifice of a house, he was laid to rest there, disposed in an eccentric artwork that also included bookshelves and a separate artwork depicting a dog.

I learned this from a book: Joseph Brent’s Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993). This picture of its pages amounts to another display: a trophy gallery of Brent’s expedition through Peirce’s thought and the archives of the Pike County (Pennsylvania) Historical Society. Click it to enlarge.

I learned this from a book: Joseph Brent’s Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993). This picture of its pages amounts to another display: a trophy gallery of Brent’s expedition through Peirce’s thought and the archives of the Pike County (Pennsylvania) Historical Society. Click it to enlarge.

If you brought a Peircian disposition to the click, you might be able to think of it as an index of me. Shining through a diffuser at the left of the image, for instance, is the brilliant tropical sunlight of Hawaii, where I happen to live. At the top can be seen the property stamp of the Hawaii State Public Library System, where I happen to get delivery service because my wife is a librarian there. And that metal thing at the bottom is a little plastic-and-wire book support whose appearance may signify something about a man in his seventies who still plays with school toys. Elsewhere in the image, too, thanks to sun and shadow and Photoshop, you can glimpse the texture of Indiana University Press’s twenty-two-year-old paper, still imploring the possibility of a staged dramatic reading: “(Pause. Then, with a catch in the throat:)”

But of course Peirce will remain dead. Under a steady drizzle of traces of life, that which once was Peirce has nevertheless undergone its final change. In its interior, the rain-swept stone remains dry. That incongruity between the images of life on the surface of things and the deathly actuality at their center is why elegy is always ironic, with irony’s trick of making us think one thing while knowing another.

But aren’t Napoleon’s death-rewarding Rhinemaidens cute as they frolic on their surface? Let us, as the cantors deludedly intone every Saturday morning, choose life.