The long history of events will need only a few extra moments to add the story of the dirigible America.

On the afternoon of October 15, 1910, under the command of the journalist-explorer Walter Wellman, America set off from Atlantic City in an attempt to fly the Atlantic Ocean. About seventy hours later, defeated by headwinds and engine trouble, the airship’s six crewmen climbed into their lifeboat, lowered themselves and their cat into the sea near the steamer Trent, and were rescued. Lightened by the abandonment, America rose back into the sky, drifted away, and was never seen again. You probably have permission to think “The End” and then forget.

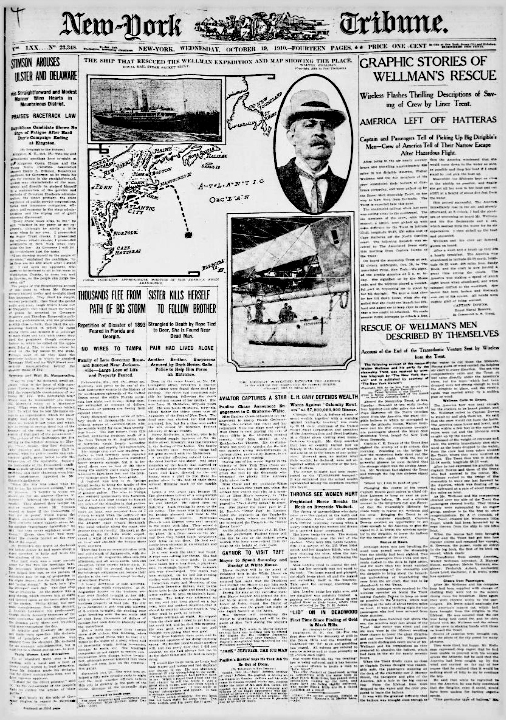

But the rescue took three hours of maneuvering in heavy seas, and during that miniature epoch somebody on board Trent was busy with a camera. As he worked, his camera filled with a growing record of a shape descending over water. Looking back at that record now, we will find ourselves wanting to penetrate its silence and find words to speak of it.

On its own, the shape within the record has already acquired at least one word. From the surrounding text which provides its historical syntax, we learn that even though America was the first aircraft to be equipped with radio, the innovation that Walter Wellman was proudest of was a device he called the equilibrator: a heavy cable suspended from the airship’s keel and towing a ton’s weight of gasoline underwater. In principle, this should have stabilized America’s altitude, compensating for the weight lost through fuel consumption by lifting its load drum by drum out of the load-supporting water. In practice, it only transferred wave motion to the airship — stressing its structure, making navigation difficult, and sickening the crew. Look through the railing around Trent’s deck and you’ll see it at its mischief, leaving a wake to port as America drifts sideways. The accumulated literal detail of this portrayal – the light suspension harness holding the umbilical cord, the foamy crease where the cord has touched the water – asks to be read as a history written in satisfyingly tragic Greek. Here, says the image, is a moral record of the moment at latitude 35.43, longitude 68.18 on October 18, 1910, when nature erased a mark made in water by overweening man. Nothing remains, now, but a now meaningless word: equilibrator.

But the record of erasure also holds a mark that hasn’t been deleted. Unwritten but inscribed, this mark endures as if it were something seen once and thereafter seen forever. It seems to have become indelible, and it seems to have achieved its indelibility by self-translation: from history to geometry.

Made accessible to reason by geometry, this form is America in two dimensions. Considered as a planar artifact, it appears to be tangent to the surface of the ocean as it descends. The representation could be a visual aid for Calculus 1: the limit instant when a vessel, descending along a curve, ceases to be of the air and becomes a creature in the first throe of metamorphosis. Light and air still embrace the surface of the falling balloon, but the waves and the equilibrator’s turbulent trace all say that the embrace will now break off and end.

It’s only an optical illusion, of course. Furthermore, any sense of human meaning in what may appear to be impending touch and consummation is a mere sentimental metaphor. In an unblemished three-dimensional image with a soundtrack, it would probably be easier for us to understand that all we’re seeing is a gaseous machine in relation to a liquid surface. Given more visual information, we would see more and have a more accurate perspective. But for some reason, only the blemished, partial, still image seems to promise us that after we see what it has recorded we will have been granted the grace to remember. At any rate, the record seems to show that from this flawed grayness America has not drifted away.

Sources:

“Wellman airship from ‘Trent.'” George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2004008853/. Photoshopped.

Peter Allen, The 91 Before Lindbergh. Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing, 1984.

On board Trent in New York after the rescue: America’s engineer Melvin Vaniman with his family and Kiddo the cat. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2004008771/. Photoshopped.

On board Trent in New York after the rescue: America’s engineer Melvin Vaniman with his family and Kiddo the cat. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2004008771/. Photoshopped.