Eras aren’t always strictly defined by their chronology. In chronological terms the Victorian era began with the ascension to the throne of Queen Victoria in 1837, but historians often date the beginning of a distinctively Victorian culture to 1832, when a parliamentary reform transferred political power definitively from the rural aristocracy to the urban middle class. It was that event which almost instantly suffused Pride and Prejudice (published only nineteen years earlier) with the nostalgia whose fumes still dizzy us when we try to read it. Eighteen thirty-two marked the moment when Pride and Prejudice became fully fictitious. Before 1832 it had been a lived-in world shared equally between its readers and their idea of its author. After 1832 it was a only a demonstration of literature’s model-maker craft: a miniature world — a museum piece behind glass, a fiction! in which the country gentleman Mr. Darcy is a knight out of Walter Scott (d. 1832) and the London lawyer Mr. Gardiner is his loyal retainer.*

Other eras are archived as other fictions, and in the course of preservation they lose some of their resemblance to the originals. The cultural history of the American 1960s, for instance, is now on display as a museum piece consisting only of the nine years, two months, and five days between November 22, 1963, when President Kennedy was killed, and January 27, 1973, when President Nixon ended the military draft. There’s something to be said, too, for the curatorial imposition of a sharp terminus between the time under museum control and the unorganized remainder of time beyond the museum. I was a graduate student at an American university during that final semester of the Sixties, and I still remember how amazing the spring light seemed when it came flooding into the air that just days earlier had been filled with the screams and sobs of the now abruptly vanished anti-war movement. For that time, time was up.

By fall, the time before the screaming began had become a nostalgia. Losing itself in the nostalgia, America toward the end of 1973 found itself aroused and bemused, almost startled, by the fierceness of its love for a movie called American Graffiti. Watch American Graffiti now and all you’ll see is a gentle little coming-of-age comedy entangled in loose plot ends. But it’s what you’ll hear on the soundtrack that made the film the phenomenon it was in 1973: an unstoppable throbbing of teen song after teen song, each one plucking the heartstrings in the rhythm of the year when it was Top 40: the year 1962, the last full year before the awfulness began. As of 1973, that rhythm was a memory of mommy’s heart, heard in the womb. Its producers supplied the rhythm with words, too, and brought audiences in with a lyric poem. “Where were you in ’62?” its lobby poster asked, and the answer that filled the throat with sobbing breath was, “In a time that can never return: the Eisenhower-Kennedy time, eleven long horrible years ago, when the world was simpler and better.”  The experience didn’t end in the fall of 1973, either. American Graffiti’s first audience demanded nostalgia encores, and the performers duly came back on stage in two of the later 1970s’ most popular TV series, Laverne and Shirley and the paradigmatically named Happy Days.

The experience didn’t end in the fall of 1973, either. American Graffiti’s first audience demanded nostalgia encores, and the performers duly came back on stage in two of the later 1970s’ most popular TV series, Laverne and Shirley and the paradigmatically named Happy Days.

But when I arrived on the campus of Detroit’s Wayne State University in September 1973, the local era there was still Sixties. In the big lobby of the building where I was now an instructor, group after group of left-wing protesters were at work, still screaming and sobbing. The screams and sobs were constants, but as you passed by the groups in turn you noticed differences. Sweetly, one group once used its little space in the taxpayers’ lobby in the middle of Detroit, the city for which the term “gritty” deserves to have been created, to hold a bake sale out of Norman Rockwell. Another group, from across the Detroit River in Windsor, Ontario, solemnly sold literature that seemed to have been translated word-for-word from Chinese, all abstract imperative clauses introduced with an adverb: “Closely follow the teachings of Comrade Enver Hoxha!” But the general tone was just ugly. There were at least two rival groups claiming to represent the Socialist Workers Party, and they used to get into fistfights with each other and then write letters about their exploits to the student newspaper. And it was no fun to try to teach in a classroom where posters had been pasted over the windows and the light switches.

One more of the uglies was the Progressive Labor Party, with its thick bilingual newspaper, Challenge / Desafio, which sold for just a dime. If you were sensitive to prose form, you might have noticed that some of that paper’s English had an Irish rhythm, as if perhaps it had been written by a graduate of Fordham — say, a graduate of Fordham in the employ of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In the quiet of the faculty lounge, I used to take up that idea with the leader of the Progressive Laborites who worked my building’s lobby.

That vendor of Challenge / Desafio was fully entitled to sit on the lounge’s vinyl furniture because she too was an instructor in Wayne’s Department of English: a witty, sophisticated young woman, Jewish like me, and fun to talk with about anything except politics. That exception naturally enough reminded me of something well known by the mid-1970s, and I did, several times, ask the papergirl, “Are you FBI?”

And she would reply, every time, “So you think I’m FBI?”

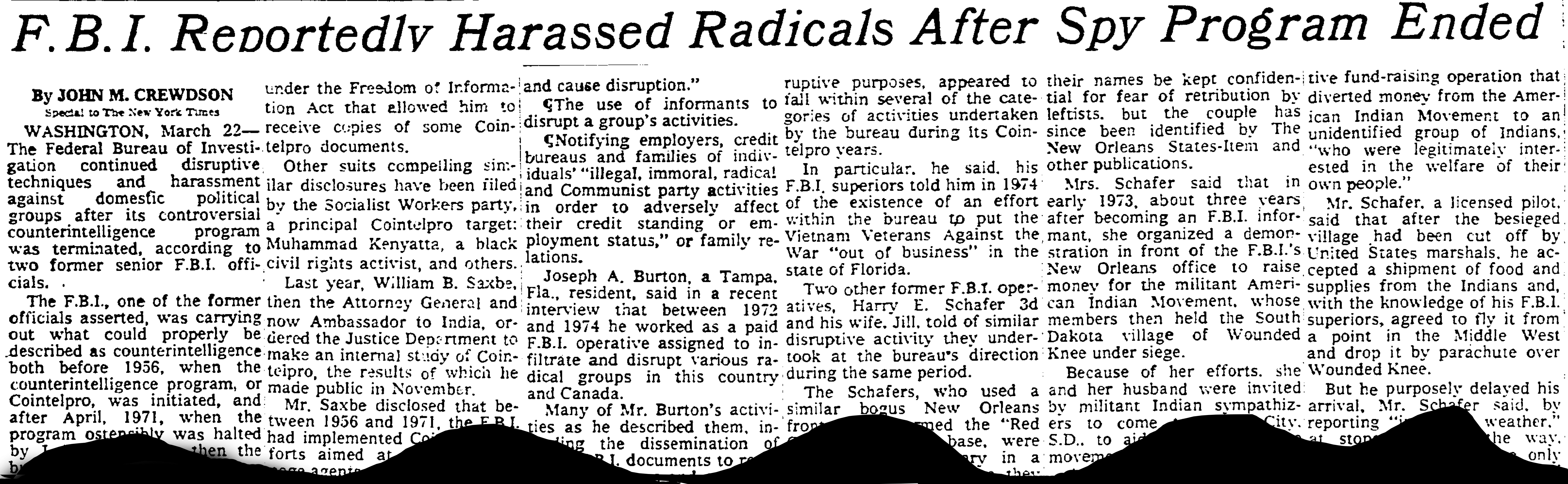

Downstairs in the lobby the screams and sobs were continuing without a break. However, on March 23, 1975, the New York Times carried this headline —  — and one morning not long after that, the lobby suddenly went silent. Overnight, the protesters were gone — all of them, every one without exception and every one at the same time. A year and a half after the Seventies arrived in the rest of the United States, they arrived at Wayne State University, thanks (I suppose) to the expiration of the subsidy the Sixties in their lobby had received from the U. S. Department of Justice. You could think of that as a funding grant for an experiment in museum science.

— and one morning not long after that, the lobby suddenly went silent. Overnight, the protesters were gone — all of them, every one without exception and every one at the same time. A year and a half after the Seventies arrived in the rest of the United States, they arrived at Wayne State University, thanks (I suppose) to the expiration of the subsidy the Sixties in their lobby had received from the U. S. Department of Justice. You could think of that as a funding grant for an experiment in museum science.

—

I’m writing this anecdote now because the historical record has now been opened a few more millimeters. The world first learned about COINTELPRO, the FBI’s campaign of anti-left harassment, in 1971, after a group of radicals burglarized an FBI office and published the documents it had found there. Until now, the radicals were never identified. As of 2014, however, some of them have come forward. In 2014 it’s possible to think of them as patriot heroes. And about that thought my anecdote comes with two PS’s.

The first I didn’t get to formulate until 1990, long after I had left Wayne State. Then, however, Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall published a collection of documents from the FBI’s files, and from there I learned that COINTELPRO had indeed been active at Wayne State. Specifically, it was active against my departmental colleague David Herreshoff.

David was a tall, gentle man and an old-fashioned socialist in the Norman Thomas tradition. In his slow, quiet bass, he would always say, “Yes, but under socialism . . .” Otherwise, he showed his radicalism by riding to campus on a bicycle and not wearing a tie. He also spent one sabbatical year in the forests of British Columbia, where he built himself a shack to live in and came to the conclusion that Thoreau was right.

About him, FBI agents wrote scurrilous unsigned letters on plain paper to Wayne State’s Board of Governors.

And about postscript 2: I completed my dissertation early in my time at Wayne State, was promoted per contract to assistant professor, and then moved on to the University of Hawaii in 1977. Meanwhile, all I could ever learn about my fellow instructor’s dissertation was that it was going to be about Langston Hughes. She never completed it, so far as I know, and per contract she was let go after the expiration of her allotted time as an instructor.

But one sunny day toward the end of my last term at Wayne State I ran into her on the street. “It’s nice to see you!” I cried. “What are you doing now?”

And the former Progressive Labor Party papergirl giggled and replied, “Oh, I’m working for Social Security.”

Note:

* For a Victorian counterexample, consider Dickens’s Bleak House (1852-53), where the country gentleman Sir Leicester Dedlock is a bewildered anachronism, the real power is wielded by the London lawyer Mr. Tulkinghorn, and (to boot) two of the villains, Harold Skimpole and Mr. Turveydrop, are scornfully depicted as caricatures of attitudes left over from Romanticism and the Regency.

Sources:

Churchill, Ward, and Jim Vander Wall. The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret War against Domestic Dissent. Boston: South End Press, 1990.

Crewdson, John M. “F.B.I. Reportedly Harassed Radicals After Spy Program Ended.” New York Times 23 March 1975. Online.

Mazzetti, Mark. “Burglars Who Took on F.B.I. Abandon Shadows.” New York Times 7 January 2014. Online.

—

Addendum, November 27, 1915:

This eulogy for David Herreshoff was published online in 2010. It will be seen that I was wrong in calling David merely a Norman Thomas socialist. I wasn’t wrong about his sweetness and gentleness, though.