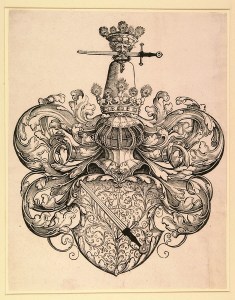

Circa 1500, the arms of Nürnberg’s patrician Kress von Kressenstein family push to the front of this wood engraving by Dürer. They are silent, but visual swagger utters on their behalf. What they mean is to be understood armigerously, as a supplemented graphic of a sword in the grip of fangs.

But not all the scions of the Kress von Kressenstein family have had the fortitude to remain in that picture. We know cousin Clara Kress von Kressenstein’s date of death, for instance (it is 1476), but her date of birth seems to have missed inclusion. Likewise, her date of death came too soon for Dürer (b. 1471). The surviving remnant of Clara’s poor premature image isn’t an approach to the Platonic, as it might have become in Dürer’s studio; it’s only somebody else’s amateur try at drawing a picture of some Clara or other. At that, we have to hope it isn’t accurate.

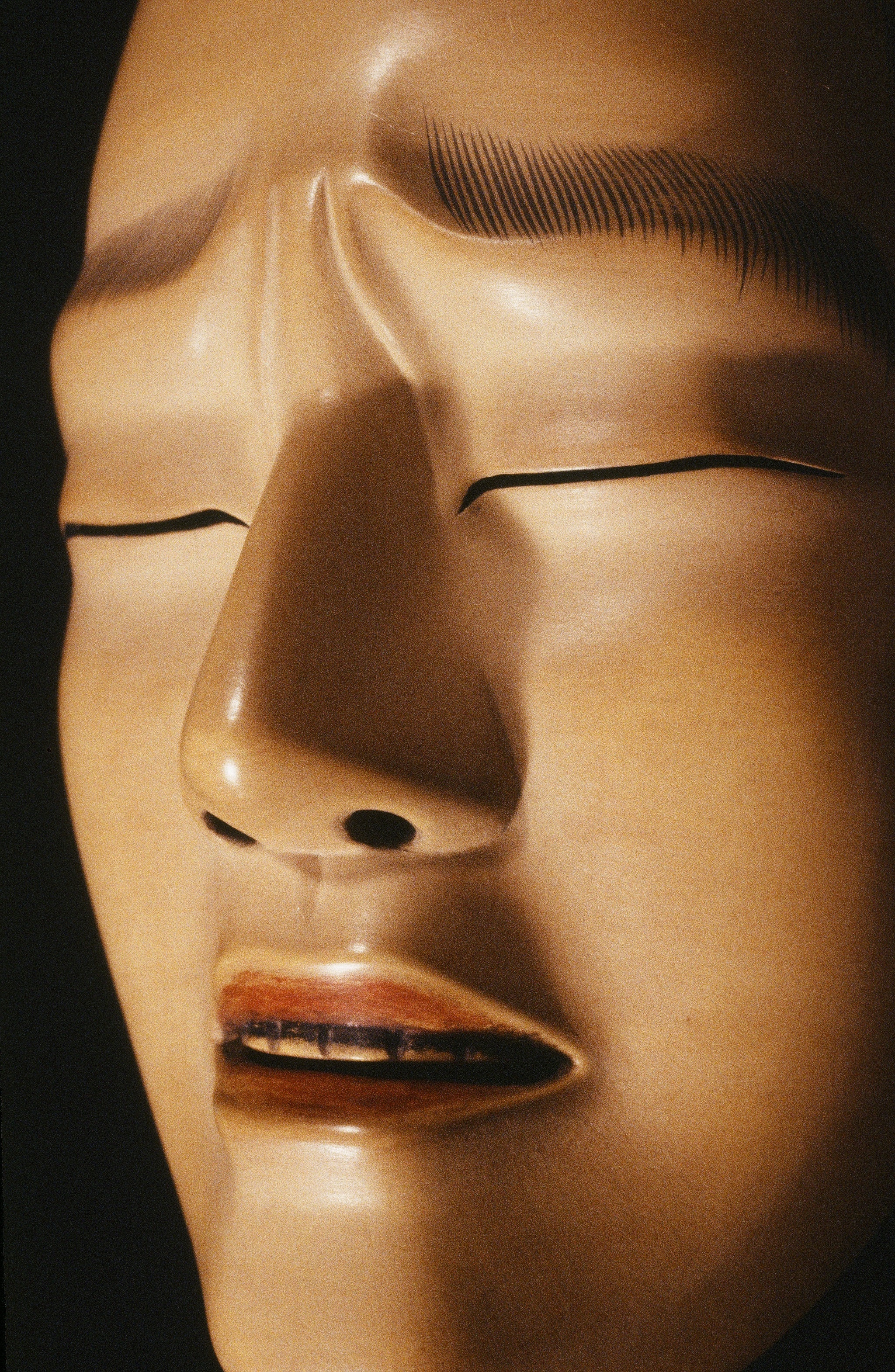

Its failure isn’t that in this depiction Clara’s face doesn’t look like a face; it’s that it looks like nothing but a face, in isolation. It seems disconnected from the rest of Clara’s body: a candidate for transplant not yet connected to a circulatory system but strapped onto a calvarium like a Noh actor’s mask. At that, a Noh mask’s disconnection from individuality is part of a harmonized ensemble of uncoupling which represents something like Platonic generalization from the real into the super-real, while the Clara mask doesn’t represent, at all. The Noh actor’s masked body moves in rule-bound play — it enters the performing space from a runway, functions dramatically there for a set time, and then departs — but the Clara body seems only to be: static, unplayful, merely forever. Solitary within its black block, it neither acts nor is acted upon. Its integuments, too, are only a layer, paper doll style. Just behind Clara’s round face is her entirely flat body. It hasn’t filled even the little space allotted to it by the optical illusion of 3D. It is only a masked nakedness.

In his introduction to Certain Noble Plays of Japan, Yeats commits a theoretical generalization on behalf of masking. “A mask,” he declares, “never seems but a dirty face, and no matter how close you go is still a work of art.” But Clara’s personal mask seems inadequately theorized, for it has been processed by art without having been made clean. A Noh mask is a drama in itself, a representation of a mind forever becoming an idea,

but what we see of the Clara mask is only a current event. It conceals no past which might give its present a meaning. Whatever it is can’t be entered into. It has no idea of that because it has no idea.

Nevertheless, within its black block it continues floating above jewels and a gown and, below the block, a separate stratum of words that speak of Clara — or rather, not of Clara but, grudgingly ill-justified, of Clara’s father and Clara’s consort. Of course they didn’t directly communicate with Clara in the black, because they couldn’t. Black on black in the flatness of inner space, words won’t form. If they could, they might record Clara’s story. Then and only then, if writing could cut itself free from its black matrix on the page and crawl upward toward the light, we might finally begin reading the story of what went on until then, behind the mask, in the dark. But after 550 years, Clara’s black mandate is still in effect.