Pre-footnote: after the widely unpredicted Republican victory in the presidential election of 2016, many media organizations in the United States dispatched pundits to rural precincts to learn what they had missed. Soon derided by the pundits themselves as “Cletus-hunting,” these expeditions typically involved respectful interviews with citizens lamenting their loss of economic and cultural status and placing the blame on urban elites. Typically, the pundits then wrote up the color red (as in the citizens’ Donald Trump wear) but not the color black (as in Barack Obama’s unclothed skin).

That coverage was truncated not only spectrally but historically. On the record of American history, the cultural conflict between pastoral and anti-pastoral had begun taking specifically literary form at least as early as Crèvecoeur’s Sketches of Eighteenth-Century America, with its fictitious political playlet about the sanctimonious neighbors who in non-fictional actual history forced Crèvecoeur to flee his farm and then stole it. The depiction of helpless fury in the face of cant was to become a distinctive genre trait which reproduced itself throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in such novels as E. W. Howe’s The Story of a Country Town, Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, and of course Huckleberry Finn. As a mode of reading, the genre remains vigorous. Three anti-Red texts still culturally resonant post-centenary are Willa Cather’s “The Sculptor’s Funeral,” Ring Lardner’s “Haircut,” and H. L. Mencken’s “The Husbandman.” Listen, Fox:

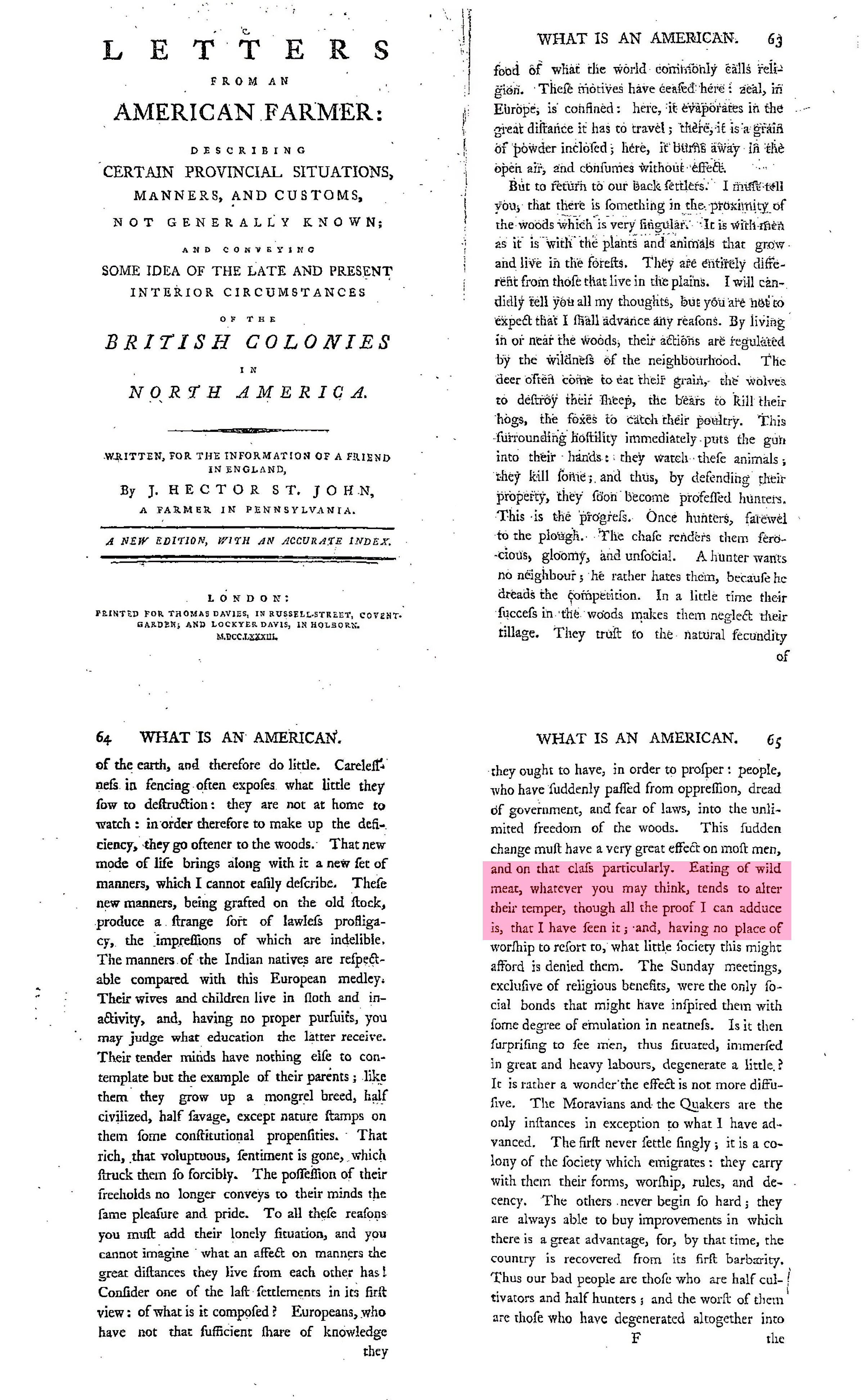

And long before Mencken, St. John Crèvecoeur, an eighteenth-century Physiocrat who believed that wealth originated in a pastoral economics of the soil, redefined those who had moved beyond the frontiers of American society as not only post-pastoral but pre-human. More than a century before Max Nordau popularized the term, Crèvecoeur was calling such life forms degenerate. Said he: the degenerates have reverted to an earlier state, of society and of body. Observe what they metabolize, there among the foxes.

After you’ve read this, the Capitol on January 6, 2021, may come to mind, with the shit smeared on the interior walls, the human space. But because there are schools on your side of the frontier, you also have learned to turn off the TV, turn back the clock, and read this twentieth-century poem.

Less than two years from this date of publication, the Great Depression will arrive to wipe the dimpled smile off Mr. Blige’s face. But it already looks like a forced smile. Mr. Blige can’t be happy in his apron among the orange squeezers. You see that in the drawing, but you can also hear it in the lyric. Back-translated to prose, O. Blige is proud but poor, loud but little, ever going over his inventory, never peacefully asleep. Rhyming itself into being, his poem has sung him so.

So take the poem seriously, at its rhymes’ words. Don’t let it get its metrical feet on an AR-15. If you do, it will communicate its rhythm to you.